RAID

RAID is an acronym that stands for Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks or Redundant Array of Independent Disks. RAID is a term used in computing. With RAID, several hard disks are made into one logical disk. There are different ways this can be done. Each of the methods that puts the hard disks together has some benefits and drawbacks over using the drives as single disks, independent of each other. The main reasons why RAID is used are:

- To make the loss of data happen less often. This is done by having several copies of the data.

- To get more storage space by having many smaller disks.

- To get more flexibility (Disks can be changed or added while the system keeps running)

- To get the data more quickly.

It is not possible to achieve all of these goals at the same time, so choices need to be made.

There are also some bad things:

- Certain choices can protect against data being lost because one (or a number) of disks failed. They do not protect against the data being deleted or overwritten, though.

- In some configurations, RAID can tolerate that one or a number of disks fail. After the failed disks have been replaced, the data needs to be reconstructed. Depending on the configuration and the size of the disks, this reconstruction can take a long time.

- Certain kinds of errors will make it impossible to read the data

Most of the work on RAID is based on a paper written in 1988.[1]

Companies have used RAID systems to store their data since the technology was made. There are different ways in which RAID systems can be made. Since its discovery, the cost of building a RAID system has come down a lot. For this reason, even some computers and appliances that are used at home have some RAID functions. Such systems can be used to store music or movies, for example.

Introduction

[change | change source]Difference between physical Disks and logical disks

[change | change source]A hard disk is a part of a computer. Normal hard disks use magnetism to store information. When hard disks are used, they are available to the operating system. In Microsoft Windows, each hard disk will get a drive letter (starting with C:, A: or B: are reserved for floppy drives). Unix and Linux-like operating systems have a single-rooted directory tree. This means that people who use the computers sometimes do not know where the information is stored.

In computing, the hard disks (which are hardware, and can be touched) are sometimes called physical drives or physical disks. What the operating system shows the user is sometimes called logical disk. A physical drive can be split into different sections, called disk partitions. Usually, each disk partition contains one file system. The operating system will show each partition like a logical disk.

Therefore, to the user, both the setup with many physical disks and the setup with many logical disks will look the same. The user cannot decide if a "logical disk" is the same as a physical disk, or if it simply is a part of the disk. Storage Area Networks (SANs) completely change this view. All that is visible of a SAN is a number of logical disks.

Reading and writing data

[change | change source]In the computer, data is organised in the form of bits and bytes. In most systems, 8 bits make up a byte. Computer memory uses electricity to store the data, hard disks use magnetism. Therefore, when data is written on a disk, the electric signal is converted into a magnetic one. When data is read from disk, the conversion is done in the other direction: An electrical signal is made from the polarity of a magnetic field.

What is RAID?

[change | change source]A RAID array joins two or more hard disks so that they make a logical disk. There are different reasons why this is done. The most common ones are:

- Stopping data loss, when one or more disks of the array fail.

- Getting faster data transfers.

- Getting the ability to change disks while the system keeps running.

- Joining several disks to get more storage capacity; sometimes lots of cheap disks are used, rather than a more expensive one.

RAID is done by using special hardware or software on the computer. The joined hard disks will then look like one hard disk to the user. Most RAID levels increase the redundancy. This means that they store the data more often, or they store information on how to reconstruct the data. This allows for a number of disks to fail without the data being lost. When the failed disk is replaced, the data it should contain will be copied or rebuilt from the other disks of the system. This can take a long time. The time it takes depends on different factors, like the size of the array.

Why use RAID?

[change | change source]One of the reasons why many companies are using RAID is that the data in the array can simply be used. Those using the data need not be aware they are using RAID at all. When a failure occurred and the array is recovering, access to the data will be slower. Accessing the data during this time will also slow down the recovery process, but this is still much faster than not being able to work with the data at all. Depending on the RAID level however, disks may not fail while the new disk is being prepared for use. A disk failing at that time will result in losing all the data in the array.

The different ways to join disks are called RAID levels. A bigger number for the level is not necessarily better. Different RAID levels have different purposes. Some RAID levels need special disks and special controllers.

History

[change | change source]In 1978, a man called Norman Ken Ouchi, who worked at IBM, made a suggestion describing the plans for what would later become RAID 5. The plans also described something similar to RAID 1, as well as the protection of a part of RAID 4.

Workers at the University of Berkeley helped to plan out research in 1987. They were trying to make it possible for RAID technology to recognize two hard drives instead of one. They found that when RAID technology had two hard drives, it had much better storage than with only one hard drive. However, it crashed much more often.

In 1988, the different types of RAID (1 to 5), were written about by David Patterson, Garth Gibson and Randy Katz in their article, called "A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID)".[1] This article was the first to call the new technology RAID and the name became official.

Basic concepts used by RAID systems

[change | change source]RAID uses a few basic ideas, which were described in the article "RAID: High-Performance, Reliable Secondary Storage" by Peter Chen and others, published in 1994.[2]

Caching

[change | change source]Caching is a technology that also has its uses in RAID systems. There are different kinds of caches that are used in RAID systems:

- Operating system

- RAID controller

- Enterprise disk array

In modern systems, a write request is shown as done when the data has been written to the cache. This does not mean that the data has been written to the disk. Requests from the cache are not necessarily handled in the same order that they were written to the cache. This makes it possible that, if the system fails, sometimes some data has not been written to the disk involved. For this reason, many systems have a cache that is backed by a battery.

Mirroring: More than one copy of the data

[change | change source]When talking about a mirror, this is a very simple idea. Instead of the data being in only one place, there are several copies of the data. These copies usually are on different hard disks (or disk partitions). If there are two copies, one of them can fail without the data being affected (as it still is on the other copy). Mirroring can also give a boost when reading data. It will always be taken from the fastest disk that responds. Writing data is slower though, because all disks need to be updated.

Striping: Part of the data is on another disk

[change | change source]With striping, the data is split into different parts. These parts then end up on different disks (or disk partitions). This means that writing data is faster, as it can be done in parallel. This does not mean that there will not be faults, as each block of data is only found on one disk.

Error correction and faults

[change | change source]It is possible to calculate different kinds of checksums. Some methods of calculating checksums allow finding a mistake. Most RAID levels that use redundancy can do this. Some methods are more difficult to do, but they allow to not only detect the error, but to fix it.

Hot spares: using more disks than needed

[change | change source]Many of the ways to have RAID support something is called a hot spare. A hot spare is an empty disk that is not used in normal operation. When a disk fails, data can directly be copied onto the hot spare disk. That way, the failed disk needs to be replaced by a new empty drive to become the hot spare.

Stripe size and chunk size: spreading the data over several disks

[change | change source]RAID works by spreading the data over several disks. Two of the terms often used in this context are stripe size and chunk size.

The chunk size is the smallest data block that is written to a single disk of the array. The stripe size is the size of a block of data that will be spread over all disks. That way, with four disks, and a stripe size of 64 kilobytes (kB), 16 kB will be written to each disk. The chunk size in this example is therefore 16 kB. Making the stripe size bigger will mean a faster data transfer rate, but also a bigger maximum latency. In this case, this is the time needed to get a block of data.

Putting disk together: JBOD, concatenation or spanning

[change | change source]

Many controllers (and also software) can put disks together in the following way: Take the first disk, till it ends, then they take the second, and so on. In that way, several smaller disks look like a larger one. This is not really RAID, as there is no redundancy. Also, spanning can combine disks where RAID 0 cannot do anything. Generally, this is called just a bunch of disks (JBOD).

This is like a distant relative of RAID because the logical drive is made of different physical drives. Concatenation is sometimes used to turn several small drives into one larger useful drive. This can not be done with RAID 0. For example, JBOD could combine 3 GB, 15 GB, 5.5 GB, and 12 GB drives into a logical drive at 35.5 GB, which is often more useful than the drives alone.

In the diagram to the right, data are concatenated from the end of disk 0 (block A63) to the beginning of disk 1 (block A64); end of disk 1 (block A91) to the beginning of disk 2 (block A92). If RAID 0 were used, then disk 0 and disk 2 would be truncated to 28 blocks, the size of the smallest disk in the array (disk 1) for a total size of 84 blocks.

Some RAID controllers use JBOD to talk about working on drives without RAID features. Each drive shows up separately in the operating system. This JBOD is not the same as concatenation.

Many Linux systems use the terms "linear mode" or "append mode". The Mac OS X 10.4 implementation — called a "Concatenated Disk Set" — does not leave the user with any usable data on the remaining drives if one drive fails in a concatenated disk set, although the disks otherwise operate as described above.

Concatenation is one of the uses of the Logical Volume Manager in Linux. It can be used to create virtual drives.

Drive Clone

[change | change source]Most modern hard disks have a standard called Self-Monitoring, Analysis and Reporting Technology (S.M.A.R.T). SMART allows to monitor certain things on a hard disk drive. Certain controllers allow to replace a single hard disk even before it fails, for example because S.M.A.R.T or another disk test reports too many correctable errors. To do this, the controller will copy all the data onto a hot spare drive. After this, the disk can be replaced by another (which will simply become the new hot spare).

Different setups

[change | change source]The setup of the disks and how they use the techniques above affects the performance and reliability of the system. When more disks are used, one of the disks is more likely to fail. Because of this, mechanisms have to be built to be able to find and fix errors. This makes the whole system more reliable, as it is able to survive and repair the failure.

Basics: simple RAID levels

[change | change source]RAID levels in common use

[change | change source]RAID 0 "striping"

[change | change source]RAID 0 is not really RAID because it is not redundant. With RAID 0, disks are simply put together to make a large disk. This is called "striping". When one disk fails, the whole array fails. Therefore, RAID 0 is rarely used for important data, but reading and writing data from the disk can be faster with striping because each disk reads part of the file at the same time.

With RAID 0, disk blocks that come after one another are usually placed on different disks. For this reason, all disks used by a RAID 0 should be the same size.

RAID 0 is often used for Swapspace on Linux or Unix-like operating systems.

RAID 1 "mirroring"

[change | change source]With RAID 1, two disks are put together. Both hold the same data, one is "mirroring" the other. This is easy, fast configuration whether implemented with a hardware controller or by software.

RAID 5 "striping with distributed parity"

[change | change source]RAID Level 5 is what is probably used most of the time. At least three hard disks are needed to build a RAID 5 storage array. Each block of data will be stored in three different places. Two of these places will store the block as it is, the third will store a checksum. This checksum is a special case of a Reed-Solomon code that only uses bitwise addition. Usually, it is calculated using the XOR method. Since this method is symmetric, one lost data block can be rebuilt from the other data block and the checksum. For each block, a different disk will hold the parity block which holds the checksum. This is done to increase redundancy. Any disk can fail. Overall, there will be one disk holding the checksums, so the total usable capacity will be that of all disks except for one. The size of the resulting logical disk will be the size of all disks together, except for one disk which holds parity information.

Of course this is slower than RAID level 1, since on every write, all disks need to be read to calculate and update the parity information. The read performance of RAID 5 is almost as good as RAID 0 for the same number of disks. Except for the parity blocks, the distribution of data over the drives follows the same pattern as RAID 0. The reason RAID 5 is slightly slower is that the disks must skip over the parity blocks.

A RAID 5 with a failed disk will continue to work. It is in degraded mode. A degraded RAID 5 can be very slow. For this reason an additional disk is often added. This is called hot spare disk. If a disk fails, the data can be directly rebuilt onto the extra disk. RAID 5 can also be done in software quite easily.

Mainly because of performance problems of failed RAID 5 arrays, some database experts have formed a group called BAARF—the Battle Against Any Raid Five.[3]

If the system fails while there are active writes, the parity of a stripe may become inconsistent with the data. If this is not repaired before a disk or block fails, data loss may occur. An incorrect parity will be used to reconstruct the missing block in that stripe. This problem is sometimes known as the "write hole". Battery-backed caches and similar techniques are commonly used to reduce the chance for this to occur.

Pictures

[change | change source]-

RAID 0 simply puts the different blocks on the different disks. There is no redundancy.

-

With Raid 1 every block is there on both disks

-

RAID 5 calculates special checksums for the data. Both the blocks with the checksum and those with the data are distributed over all disks.

RAID levels used less

[change | change source]RAID 2

[change | change source]This was used with very large computers. Special expensive disks and a special controller are needed to use RAID Level 2. The data is distributed at the bit-level (all other levels use byte-level actions). Special calculations are done. Data is split up into static sequences of bits. 8 data bits and 2 parity bits are put together. Then a Hamming code is calculated. The fragments of the Hamming code are then distributed over the different disks.

RAID 2 is the only RAID level that can repair errors, the other RAID levels can only detect them. When they find that the information needed does not make sense, they will simply rebuild it. This is done with calculations, using information on the other disks. If that information is missing or wrong, they cannot do much. Because it uses Hamming codes, RAID 2 can find out which piece of the information is wrong, and correct only that piece.

RAID 2 needs at least 10 disks to work. Because of its complexity and its need for very expensive and special hardware, RAID 2 is no longer used very much.

RAID 3 "striping with dedicated parity"

[change | change source]Raid Level 3 is much like RAID Level 0. An additional disk is added to store parity information. This is done by bitwise addition of the value of a block on the other disks. The parity information is stored on a separate (dedicated) disk. This is not good, because if the parity disk crashes, the parity information is lost.

RAID Level 3 is usually done with at least 3 disks. A two-disk setup is identical to a RAID Level 0.

RAID 4 "striping with dedicated parity"

[change | change source]This is very similar to RAID 3, except that the parity information is calculated over larger blocks, and not single bytes. This is like RAID 5. At least three disks are needed for a RAID 4 array.

RAID 6

[change | change source]RAID level 6 was not an original RAID level. It adds an additional parity block to a RAID 5 array. It needs at least four disks (two disks for the capacity, two disks for redundancy). RAID 5 can be seen as a special case of a Reed-Solomon code. RAID 5 is a special case, though, it only needs addition in the Galois field GF(2). This is easy to do with XORs. RAID 6 extends these calculations. It is no longer a special case, and all of the calculations need to be done. With RAID 6, an extra checksum (called polynomial) is used, usually of GF (28). With this approach it is possible to protect against any number of failed disks. RAID 6 is for the case of using two checksums to protect against the loss of two disks.

Like with RAID 5, parity and data are on different disks for each block. The two parity blocks are also located on different disks.

There are different ways to do RAID 6. They are different in their write performance, and in how much calculations are needed. Being able to do faster writes usually means more calculations are needed.

RAID 6 is slower than RAID 5, but it allows the RAID to continue with any two disks failed. RAID 6 is becoming popular because it allows an array to be rebuilt after a single-drive failure even if one of the remaining disks has one or more bad sectors.

Pictures

[change | change source]-

RAID 3 is much like RAID level 0. An extra disk is added that will hold a checksum for each block of data.

-

RAID 4 is similar to RAID level 3, but calculates parity over larger blocks of data

-

RAID 6 is similar to RAID 5, but it calculates two different checksums. This allows for two disks to fail, without data loss.

Non-standard RAID levels

[change | change source]Double parity / Diagonal parity

[change | change source]RAID 6 uses two parity blocks. These are calculated in a special way over a polynomial. Double parity RAID (also called diagonal parity RAID)[4] uses a different polynomial for each of these parity blocks. Recently, the industry association that defined RAID said that double parity RAID is a different form of RAID 6.

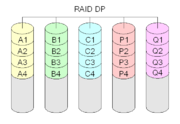

RAID-DP

[change | change source]RAID-DP is another way of having double parity.

RAID 1.5

[change | change source]RAID 1.5 (not to be confused with RAID 15, which is different) is a proprietary RAID implementation. Like RAID 1, it only uses two disks, but it does both striping and mirroring (similar to RAID 10). Most things are done in hardware.

RAID 5E, RAID 5EE and RAID 6E

[change | change source]RAID 5E, RAID 5EE and RAID 6E (with the added E for Enhanced) generally refer to different types of RAID 5 or RAID 6 with a hot spare. With these implementations, the hot spare drive is not a physical drive. Rather, it exists in the form of free space on the disks. This increases performance, but it means that a hot spare cannot be shared between different arrays. The scheme was introduced by IBM ServeRAID around 2001.[5]

RAID 7

[change | change source]This is a proprietary implementation. It adds caching to a RAID 3 or RAID 4 array.[6]

Intel Matrix RAID

[change | change source]Some Intel main boards have RAID chip that have this feature. It uses two or three disks, and then partitions them equally to form a combination of RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 5 or RAID 1+0 levels.

Linux MD RAID driver

[change | change source]This is the name for the driver that allows to do software RAID with Linux. In addition to the normal RAID levels 0-6, it also has a RAID 10 implementation. Since Kernel 2.6.9, RAID 10 is a single level.[7] The implementation has some non-standard features.[8]

RAID Z

[change | change source]Sun has implemented a file system called ZFS. This file system is optimised for handling large amounts of data. It includes a Logical Volume Manager. It also includes a feature called RAID-Z. It avoids the problem called RAID 5 write hole [9] because it has a copy-on-write policy: It does not overwrite the data directly, but writes new data in a new location on the disk. When the write was successful, the old data is deleted. It avoids the need for read-modify-write operations for small writes, because it only writes full-stripes. Small blocks are mirrored instead of parity protected, which is possible because the file system knows the way the storage is organised. It can therefore allocate extra space if necessary. There is also RAID-Z2 which uses two forms of parity to achieve results similar to RAID 6: the ability to survive up to two drive failures without losing data.[10]

Pictures

[change | change source]-

Diagram of a RAID DP (Double Parity) setup.

-

A Matrix RAID setup.

Joining RAID levels

[change | change source]With RAID different disks can be put together to get a logical disk.The user will only see the logical disk. Each one of the RAID levels mentioned above has good and bad points. But RAID can also work with logical disks. That way one of the RAID levels above can be used with a set of logical disks. Many people note it by writing the numbers together. Sometimes, they write a '+' or an '&' in between. Common combinations (using two levels) are the following:

- RAID 0+1: Two or more RAID 0 arrays are combined to a RAID 1 array; This is called a Mirror of stripes

- RAID 1+0: Same as RAID 0+1, but RAID levels reversed; Stripe of Mirrors. This makes disk failure rarer than RAID 0+1 above.

- RAID 5+0: Stripe several RAID 5's with a RAID 0. One disk of each RAID 5 can fail, but makes that RAID 5 the single point of failure; if another disk of that array fails, all the data of the array will be lost.

- RAID 5+1: Mirror a set of RAID 5: In a situations where the RAID is made of six disks, any three can fail (without data being lost).

- RAID 6+0: Stripe several RAID 6 arrays over a RAID 0; Two disks of each RAID 6 can fail without data loss.

With six disks of 300 GB each, a total capacity of 1.8TB, it is possible to make a RAID 5, with 1.5 TB usable space. In that array, one disk can fail without data loss. With RAID 50, the space is reduced to 1.2 TB, but one disk of each RAID 5 can fail, plus there is a noticeable increase in performance. RAID 51 reduces the usable size to 900 GB, but allows any three drives to fail.

-

RAID 0+1: Several RAID 0 arrays are combined with a RAID 1

-

RAID 1+0: More robust than RAID 0+1; supports multiple drive failures, as long as no two drives that make a mirror fail.

-

RAID 5+1: Any three drives of this can fail, without data loss.

Making a RAID

[change | change source]There are different ways to make a RAID. It can either be done with software, or with hardware.

Software RAID

[change | change source]A RAID can be made with software in two different ways. In the case of Software RAID, the disks are connected like normal hard disks. It is the computer that makes the RAID work. This means that for each access the CPU also needs to do the calculations for the RAID. The calculations for RAID 0 or RAID 1 are simple. However, the calculations for RAID 5, RAID 6, or one of the combined RAID levels can be a lot of work. In a software RAID, automatically booting from an array that failed may be a difficult thing to do. Finally, the way RAID is done in software depends on the operating system used; it is generally not possible to re-build a Software RAID array with a different operating system. Operating systems usually use hard disk partitions rather than whole hard disks to make RAID arrays.

Hardware RAID

[change | change source]A RAID can also be made with hardware. In this case, a special disk controller is used; this controller card hides the fact that it is doing RAID from the operating system and the user. The calculations of checksum information, and other RAID-related calculations are done on a special microchip in that controller. This makes the RAID independent of the operating system. The operating system will not see the RAID, it will see a single disk. Different manufacturers do RAID in different ways. This means that a RAID built with one hardware RAID controller cannot be rebuilt by another RAID controller of a different manufacturer. Hardware RAID controllers are often expensive to buy.

Hardware-assisted RAID

[change | change source]This is a mix between hardware RAID and software RAID. Hardware-assisted RAID uses a special controller chip (like hardware RAID), but this chip can not do many operations. It is only active when the system is started; as soon as the operating system is fully loaded, this configuration is like software RAID. Some motherboards have RAID functions for the disks attached; most often, these RAID functions are done as hardware-assisted RAID. This means that special software is needed to be able to use these RAID functions and to be able to recover from a failed disk.

Different terms related to hardware failures

[change | change source]There are different terms that are used when talking about hardware failures:

Failure rate

[change | change source]The failure rate is how often a system fails. The mean time to failure (MTTF) or mean time between failures (MTBF) of a RAID system is the same as that of its components. A RAID system cannot protect against failures of its individual hard drives, after all. The more complicated types of RAID (anything beyond "striping" or "concatenation") can help keep the data intact even if an individual hard drive fails, though.

Mean time to data loss

[change | change source]The mean time to data loss (MTTDL) gives the average time before a loss of data happens in a given array.[11] Mean time to data loss of a given RAID may be higher or lower than that of its hard disks. This depends on the type of RAID used.

Mean time to recovery

[change | change source]Arrays that have redundancy can recover from some failures. The mean time to recovery shows how long it takes until a failed array is back to its normal state. This adds both the time to replace a failed disk mechanism as well as time to re-build the array (i.e. to replicate data for redundancy).

Unrecoverable bit error rate

[change | change source]The unrecoverable bit error rate (UBE) tells how long a disk drive will be unable to recover data after using cyclic redundancy check (CRC) codes and multiple retries.

Problems with RAID

[change | change source]There are also certain problems with the ideas or the technology behind RAID:

Adding disks at a later time

[change | change source]Certain RAID levels allow to extend the array by simply adding hard disks, at a later time. Information such as parity blocks is often scattered on several disks. Adding a disk to the array means that a reorganisation becomes necessary. Such a reorganisation is like a re-build of the array, it can take a long time. When this is done, the additional space may not be available yet, because both the file system on the array, and the operating system need to be told about it. Some file systems do not support to be grown after they have been created. In such a case, all the data needs to be backed up, the array needs be re-created with the new layout, and the data needs to be restored onto it.

Another option to add storage is to create a new array, and to let a logical volume manager handle the situation. This allows to grow almost any RAID system, even RAID1 (which by itself is limited to two disks).

Linked failures

[change | change source]The error correction mechanism in RAID assumes that failures of drives are independent. It is possible to calculate how often a piece of equipment can fail and to arrange the array to make data loss very improbable.

In practice, however, the drives were often bought together. They have roughly the same age, and have been used similarly (called wear). Many drives fail because of mechanical problems. The older a drive is, the more worn are its mechanical parts. Mechanical parts that are old are more likely to fail than those that are younger. This means that drive failures are no longer statistically independent. In practice, there is a chance that a second disk will also fail before the first has been recovered. This means that data loss can occur at significant rates, in practice.[12]

Atomicity

[change | change source]Another problem that also occurs with RAID systems is that applications expect what is called Atomicity: Either all of the data is written, or none is. Writing the data is known as a transaction.

In RAID arrays, the new data is usually written in the place where the old data was. This has become known as update in-place. Jim Gray, a database researcher wrote a paper in 1981 where he described this problem.[13]

Very few storage systems allow atomic write semantics. When an object is written to disk, a RAID storage device will usually be writing all copies of the object in parallel. Very often, there is only one processor responsible for writing the data. In such a case, the writes of data to the different drives will overlap. This is known as overlapped write or staggered write. An error that occurs during the process of writing may therefore leave the redundant copies in different states. What is worse, it may leave the copies in neither the old nor the new state. Logging relies on the original data being either in the old or the new state, though. This permits backing out the logical change, but few storage systems provide an atomic write semantic on a RAID disk.

Using a battery-backed write cache can solve this problem, but only in a power failure scenario.

Transactional support is not present in all hardware RAID controllers. Therefore, many operating systems include it to protect against data loss during an interrupted write. Novell Netware, starting with version 3.x, included a transaction tracking system. Microsoft introduced transaction tracking via the journaling feature in NTFS. NetApp WAFL file system solves it by never updating the data in place, as does ZFS.

Unrecoverable data

[change | change source]Some sectors on a hard disk may have become unreadable because of a mistake. Some RAID implementations can deal with this situation by moving the data elsewhere and marking the sector on the disk as bad. This happens at about 1 bit in 1015 in enterprise-class disk drives, and 1 bit in 1014 in ordinary disk drives.[14] Disk capacities are steadily increasing. This may mean that sometimes, a RAID cannot be rebuilt, because such an error is found when the array is rebuilt after a disk failure. Certain technologies such as RAID 6 try to address this issue, but they suffer from a very high write penalty, in other words writing data becomes very slow.

Write cache reliability

[change | change source]The disk system can acknowledge the write operation as soon as the data is in the cache. It does not need to wait until the data has been physically written. However, any power outage can then mean a significant data loss of any data queued in such a cache.

With hardware RAID, a battery can be used to protect this cache. This often solves the problem. When the power fails, the controller can finish writing the cache when the power is back. This solution can still fail, though: the battery may have worn out, the power may have been off for too long, the disks could be moved to another controller, the controller itself could fail. Certain systems can do periodic battery checks, but these use the battery itself, and leave it in a state where it is not fully charged.

Equipment compatibility

[change | change source]The disk formats on different RAID controllers are not necessarily compatible. Therefore, it may not be possible to read a RAID array on different hardware. Consequently, a non-disk hardware failure may require using identical hardware, or a backup, to recover the data.

What RAID can and cannot do

[change | change source]This guide was taken from a thread in a RAID-related forum. This was done to help point out the advantages and disadvantages of choosing RAID. It is directed at people who want to choose RAID for either increases in performance or redundancy. It contains links to other threads in its forum containing user-generated anecdotal reviews of their RAID experiences.

What RAID can do

[change | change source]- RAID can protect uptime. RAID levels 1, 0+1/10, 5 and 6 (and their variants such as 50 and 51) make up for a mechanical hard disk failure. Even after the disk failed, the data on the array can still be used. Instead of a time consuming restore from tape, DVD or other slow backup media, RAID allows data to be restored to a replacement disk from the other members of the array. During this restoration process, it is available to users in a degraded state. This is very important to enterprises, as downtime quickly leads to lost earning power. For home users, it can protect uptime of large media storage arrays, which would require time consuming restoration from dozens of DVD or quite a few tapes in the event of a disk failing that is not protected by redundancy.

- RAID can increase performance in certain applications. RAID levels 0, 5 and 6 all use striping. This allows multiple spindles to increase transfer rates for linear transfers. Workstation-type applications often work with large files. They greatly benefit from disk striping. Examples for such applications are those using video or audio files. This throughput is also useful in disk-to-disk backups. RAID 1 as well as other striping-based RAID levels can improve the performance for access patterns with many simultaneous random accesses, like those used by a multi-user database.

What RAID cannot do

[change | change source]- RAID cannot protect the data on the array. A RAID array has one file system. This creates a single point of failure. There are many things that can happen to this file system other than physical disk failure. RAID cannot defend against these sources of data loss. RAID will not stop a virus from destroying data. RAID will not prevent corruption. RAID will not save data when a user modifies it or deletes it by accident. RAID does not protect data from hardware failure of any component besides physical disks. RAID does not protect data from natural or man made disasters such as fires and floods. To protect data, it must be backed up to removable media, such as DVD, tape, or an external hard disk. The backup must be kept in a different place. RAID alone will not prevent a disaster, when (not if) it occurs, from turning into data loss. Disasters cannot be prevented, but backups allow data loss to be prevented.

- RAID cannot simplify disaster recovery. When running a single disk, the disk can be used by most operating systems as they come with a common device driver. However, most RAID controllers need special drivers. Recovery tools that work with single disks on generic controllers will require special drivers to access data on RAID arrays. If these recovery tools are poorly coded and do not allow providing for additional drivers, then a RAID array will probably be inaccessible to that recovery tool.

- RAID cannot provide a performance boost in all applications. This statement is especially true with typical desktop application users and gamers. For most desktop applications and games the buffer strategy and seek performance of the disk(s) are more important than raw throughput. Increasing raw sustained transfer rate shows little gains for such users, as most files that they access are typically very small anyway. Disk striping using RAID 0 increases linear transfer performance, not buffer and seek performance. As a result, disk striping using RAID 0 shows little to no performance gain in most desktop applications and games, although there are exceptions. For desktop users and gamers with high performance as a goal, it is better to buy a faster, bigger, and more expensive single disk than it is to run two slower/smaller drives in RAID 0. Even running the latest, greatest, and biggest drives in RAID-0 is unlikely to boost performance more than 10%, and performance may drop in some access patterns, particularly games.

- It is difficult to move RAID to a new system. With a single disk, it is relatively easy to move the disk to a new system. It can simply be connected to the new system, if it has the same interface available. However, this is not so easy with a RAID array. There is a certain kind of Metadata that says how the RAID is set up. A RAID BIOS must be able to read this metadata so that it can successfully construct the array and make it accessible to an operating system. Since RAID controller makers use different formats for their metadata (even controllers of different families from the same manufacturer may use incompatible metadata formats) it is almost impossible to move a RAID array to a different controller. When moving a RAID array to a new system, plans should be made to move the controller as well. With the popularity of motherboard integrated RAID controllers, this is extremely difficult. Generally, it is possible to move the RAID array members and controllers together. Software RAID in Linux and Windows Server Products can also work around this limitation, but software RAID has others (mostly performance related).

Example

[change | change source]The RAID levels used most often are RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 5. Suppose there is a 3 disk setup, with 3 identical disks of 1 TB each, and the probability of failure of a drive for a given timespan is 1%.

| RAID Level | Usable capacity | Probability of failure

given in percent |

Probability of failure

1 in ... cases fail |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 TB | 2,9701% | 34 |

| 1 | 1 TB | 0,0001% | 1 million |

| 5 | 2 TB | 0,0298% | 3356 |

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ""A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks" - Patterson, Gibson, Katz" (PDF). University of California. 1988.

- ↑ "RAID: High-Performance, Reliable Secondary Storage" (PDF).

- ↑ "BAARF - Battle Against Any Raid Five". Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "RAID-DP™: Network Appliance™ implementation of RAID Double Parity for data protection, a high speed implementation of RAID 6" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "IBM X-Architecture Technology 2001:A design blueprint for Intel processor-based servers" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "RAID Level 7".

- ↑ "Linux RAID 10 driver".

- ↑ "Main Page - Linux-raid". Archived from the original on 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ "RAID-Z : Jeff Bonwick's Blog".

- ↑ "Adam Leventhal's Weblog".

- ↑ Jim Gray and Catharine van Ingen, "Empirical Measurements of Disk Failure Rates and Error Rates", MSTR-2005-166, December 2005

- ↑ Bianca Schroeder and Garth A. Gibson (2007). "Disk Failures in the Real World: What Does an MTTF of 1,000,000 Hours Mean to You?".

- ↑ Jim Gray. "The Transaction Concept: Virtues and Limitations (Invited Paper)¦format=pdf" (PDF). "VLDB 1981". Archived from the original on 2008-07-26. Retrieved 2008-08-14. 144-154

- ↑ Jim Gray; Catherine van Ingen (2007). "Empirical Measurements of Disk Failure Rates and Error Rates". arXiv:cs/0701166.

Other websites

[change | change source]- RAID 6 tutorial

- Working RAID pictures Archived 2008-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- RAID Levels — Tutorial and Diagrams Archived 2008-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Animations to learn about RAID Levels 0, 1, 5, 10, and 50 Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine