Odd Man Out is a 1947 British film noir directed by Carol Reed, and starring James Mason, Robert Newton, Cyril Cusack, and Kathleen Ryan. Set in Belfast, Northern Ireland, it follows a wounded Nationalist leader who attempts to evade police in the aftermath of a robbery. It is based on the 1945 novel of the same name by F. L. Green.[4]

| Odd Man Out | |

|---|---|

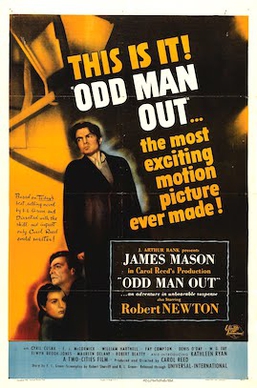

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Carol Reed |

| Written by | R. C. Sherriff |

| Based on | Odd Man Out 1945 novel by F. L. Green |

| Produced by | Carol Reed |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Fergus McDonell |

| Music by | William Alwyn |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | >US$1 million[2] |

| Box office | US$1.25 million (US rentals)[3] |

The film received the first BAFTA Award for Best British Film, and was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Film Editing. Filmmaker Roman Polanski repeatedly cited Odd Man Out as his favourite film.

Odd Man Out follows the Mason character "on an anguished journey through the alleys of Belfast that visually presages Harry Lime's shadowy flight through the sewers of Vienna" in Reed's 1949 film The Third Man.[5]

Plot

editIrish nationalist 'organisation' member Johnny McQueen has been hiding for six months, since his escape from prison, in a house occupied by Kathleen Sullivan (who has fallen in love with Johnny) and her grandmother. He is ordered to rob a mill but his seclusion makes his men question his fitness; his lieutenant Dennis offers to take his place, but Johnny turns him down.

Johnny, Nolan, and Murphy carry out the robbery, While fleeing, Johnny falls behind the others and is tackled by an armed guard, whom he kills. Johnny is shot in the shoulder. He is pulled into the car, but falls out. Pat, the getaway driver, refuses to return to retrieve him. Weak and disorientated, Johnny hides in a nearby air raid shelter.

After telling Dennis what happened, Nolan, Murphy and Pat leave for "headquarters." On the way they are seen by police and pursued. Pat and Nolan stop off at Theresa O'Brien's well-to-do guest house, but Murphy does not trust her and goes elsewhere. Theresa betrays Pat and Nolan, who are killed in a gunfight with police.

Dennis finds Johnny, but the police show up nearby. Dennis is captured after drawing them away.

Johnny makes his way toward Kathleen's place, but collapses in the street. Passers-by Maureen and Maudie take him home, thinking he has been struck by a passing lorry. They attempt to give first-aid then see it is a gunshot wound, realising who they have found as the husband returns. An argument over what to do starts, Johnny hears their debate and departs, getting into a parked hansom cab. "Gin" Jimmy, the cab driver, comes out and starts looking for a fare, unaware he already has a wanted man for a passenger. When he finds out, he abandons Johnny in a vacant lot.

Shell spots him dumping the now nearly unconscious fugitive. He goes to Catholic priest Father Tom, hoping for a financial reward. Kathleen arrives shortly afterward, looking for help. Father Tom persuades Shell to fetch Johnny. Upon returning home, Shell has to fend off another resident, the eccentric painter Lukey, who wants him to pose for a portrait again; an argument starts between them. Meanwhile, Johnny revives and stumbles into a local pub where he is recognised by the landlord, who quickly deposits Johnny in a snug where no one else will see him, with the intention of getting rid of him later. Shell and Lukey who separately have converged on the bar start a fight with each other. Fencie breaks it up, closes for the evening, and persuades Lukey to take Johnny away as compensation for the damage he caused the pub. Lukey takes Johnny back to his studio to paint his portrait. Failed medical student Tober tends to Johnny's wound, and he flees.

Kathleen slips away from Father Tom during the visit to the rectory by a police inspector hunting for Johnny. She arranges passage on a ship for Johnny and goes searching for him. Shell starts Johnny toward Father Tom's, and Johnny encounters Kathleen. She takes Johnny toward the ship but sees the police closing in. She draws a gun and fires twice. The police return fire killing them both.

Cast

edit- James Mason as Johnny McQueen

- Kathleen Ryan as Kathleen Sullivan

- Robert Newton as Lukey, the artist

- Cyril Cusack as Pat

- F. J. McCormick as Shell

- William Hartnell as Fencie the barman

- Fay Compton as Rosie

- Denis O'Dea as Inspector

- W. G. Fay as Father Tom

- Maureen Delaney as Theresa O’Brien

- Elwyn Brook-Jones as Tober

- Robert Beatty as Dennis

- Dan O'Herlihy as Nolan

- Kitty Kirwan as Grannie

- Beryl Measor as Maudie

- Roy Irving as Murphy

- Maureen Cusack as Mollie

- Maura Milligan as Cashier

- Joseph Tomelty as 'Gin' Jimmy, the cabbie

- Ann Clery as Maureen

- Eddie Byrne as Policeman

- Wilfrid Brambell as Tram Passenger (uncredited)

Production

editDevelopment

editF.L. Green's novel, also used as the basis of the 1969 Sidney Poitier film The Lost Man, was published in 1945. It followed upon wartime action by the IRA in Belfast, in consequence of which Northern Ireland undertook its first and only execution of an Irish Republican, 19-year-old Tom Williams.[6] In the novel, an IRA plot goes horribly wrong when its leader, Johnny Murtah, kills an innocent man, and he is gravely wounded. The source of Green's familiarity with the Belfast IRA at the time is thought to be the Belfast writer Denis Ireland.[7] Ireland's anti-Partition Ulster Union Club had been infiltrated by the IRA intelligence officer and recruiter John Graham.[8]

Casting

editAccording to Richard Burton, the lead role was originally offered to Stewart Granger. Burton wrote in his diaries:

Reminds me of Jimmy Granger being sent the script of Odd Man Out by Carol Reed and flipping through the pages where he had dialogue, deciding that the part wasn't long enough. He didn't notice the stage directions so turned it down and James Mason played it instead and made a career out of it. It's probably the best thing that Mason has ever done and certainly the best film he's ever been in while poor Granger has never been in a good classic film at all. Or, as far as I remember, in a good film of any kind. You could after all have a 'James Mason Festival' but you couldn't have a 'Stewart Granger' one. Except as a joke. Granger tells the story ruefully against himself.[9]

Aside from Mason, the supporting cast was drawn largely from Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Among the other members of the Organisation are Cyril Cusack, Robert Beatty, and Dan O'Herlihy. On his travels, Johnny meets an opportunistic bird-fancier played by F. J. McCormick, a drunken artist played by Robert Newton, a barman (William Hartnell) and a failed surgeon (Elwyn Brook-Jones). Denis O'Dea is the inspector on Johnny's trail, and Kathleen Ryan, in her first feature film, plays the woman who loves Johnny. Also notable are W. G. Fay—a founder of the Abbey Theatre—as the kindly Father Tom, Fay Compton, Joseph Tomelty, and Eddie Byrne. Albert Sharpe plays a bus conductor. A number of non-speaking parts were filled by actors who later achieved public attention, including Dora Bryan, Geoffrey Keen, Noel Purcell, Guy Rolfe and Wilfrid Brambell (a standing passenger in the tram scene). Few of the main actors in the film actually manage an authentic Ulster accent.

Filming

editThe cinematographer was Robert Krasker, in his first film for director Reed, lighting sets designed by Ralph Brinton and Roger Furse. Reed made extensive use of location filming, which was uncommon at the time.[10] Exterior scenes were shot in West Belfast,[11] although some were shot at Broadway Market in London.[12]

The bar set was based on the Crown Bar in Belfast but was a studio set built at D&P Studios in Denham, Buckinghamshire.[11] The duplication was so authentic that tourists in subsequent years would visit the Crown Bar, thinking it was the bar in the film. To further enhance the realism of the film, Reed used real sounds instead of standard sound effects, recording the "actual drum of mill machinery and the echo of hoof beats." The narrowness of Johnny's world is represented by scenes shot on location in small rooms and in alleys. [10]

The film went over budget and overschedule so although it was successful it hurt Reed's relationship with the Rank Organisation.[13]

Music

editComposer William Alwyn was involved writing the leitmotif-based film score from the very beginning of the production. It was performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Muir Mathieson.

Political context and censorship

editThe film did not mention the IRA by name and, like John Ford's The Informer (1935), only "casually touched on the underlying conflict." Both use the backdrop of conflict in Ireland to present morality tales designed to appeal to the broadest possible audience. The IRA was portrayed as little more than a criminal gang. Politics and the cause of Irish nationalism was avoided to "circumvent controversy and pass the censors."[14]

With an eye toward distribution of the film in the United States, the film script was submitted to Joseph Breen of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, who advised the producers that the original ending, a murder-suicide, violated the Hollywood Production Code. Years earlier, Breen had similarly submitted the script of The Informer to the British Board of Film Censors, which requested numerous changes to omit references to the Anglo-Irish conflict.[14][15]

Odd Man Out and The Informer are also similar in being "dramatic portrayals of lapsed Catholics rediscovering their lost faith," and "end with their dying protagonists assuming Christ-like poses."[5]

Writing in The IRA on Film and Television: A History, author Mark Connelly observes that Johnny is "more of a mob boss than revolutionary," and that the F.L. Green novel upon which the film was based took a dim view of Irish nationalism.[10]

Reception

editCritics

editOdd Man Out was "hailed as a masterpiece by many critics and a box office hit—at least in Europe, where Reed had gauged the mood of postwar despondency with caliper-like accuracy."[16]

New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther praised the performances and the plotting of the early sequences in the film, which he compared favorably to The Informer, but he criticized the subsequent portions of the film, which he described as "fumbled" by shifting attention away from Mason and his motivations to "cryptic characters," relieving the protagonist of his illustrative role, and "whatever it is they are proving—if anything—is anybody's guess."[4]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote "This film puts Reed high in the first rank of directors."[17]

Box office

editIt ranked eighth among more popular movies at the British box office in 1947,[18] and was one of the most successful films ever shown in South America.[5]

Awards

editThe film received the BAFTA Award for Best British Film in 1948. It was nominated for the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival in 1947, and nominated for a Best Film Editing Oscar in 1948.

| Award / Film Festival | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Film Editing | Fergus McDonell | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best British Picture | Odd Man Out | Won |

Legacy

editCarol Reed biographer Robert F. Moss notes that Odd Man Out is "almost indisputably Reed's masterpiece."[19]

Filmmaker Roman Polanski repeatedly has cited Odd Man Out as his favourite film.[20] Polanski stated that Odd Man Out is superior to The Third Man, another film that has been considered to be Reed's masterpiece:

I still consider it as one of the best movies I've ever seen and a film which made me want to pursue this career more than anything else...I always dreamt of doing things of this sort or that style. To a certain extent I must say that I somehow perpetuate the ideas of that movie in what I do.[20]

Sam Peckinpah also cited it as a personal favorite.[citation needed]

American novelist, essayist and some-time screenwriter Gore Vidal called the film a "near-perfect film" and its screenwriter R. C. Sherriff "one of the few true film auteurs."[21]

Writing in 2006, Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw gave the film three out of five stars. He wrote that the film was a "fascinating but imperfect thriller" that reflected "Belfast's forgotten identity as a bustling, prosperous provincial city, not obviously shattered by sectarianism or terrorism: a city in which a packed tram can head for the Falls Road, without any visible sense of fear."[22]

Leonard Maltin gave the movie 4 out of 4 stars naming it "Incredibly suspenseful."[citation needed]

Radio adaptation

editOdd Man Out was presented on Suspense 11 February 1952. James Mason and his wife Pamela Mason starred in the 30-minute adaptation.[23]

References

edit- ^ "Odd Man Out". The Times. 31 January 1947. p. 4.

- ^ "Thrill-type tales choice of British". Los Angeles Times. 7 July 1946. ProQuest 165714120.

- ^ "Variety (October 1947)". archive.org. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (24 April 1947). "Odd Man Out (1947) ' Odd Man Out,' British Film in Which James Mason Again Is the Chief Menace, Has Its Premiere at Loew's Criterion". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Connelly 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat (2003). Ireland in the Twentieth Century. London: Random House. p. 334. ISBN 9780099415220..

- ^ "John Graham". The Treason Felony Blog. 14 February 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). The IRA. London: Macmillan. p. 178.

- ^ Burton, Richard (24 June 1971). Richard Burton Diaries.

- ^ a b c Connelly 2012, p. 154.

- ^ a b 'BBC seeks stars of Belfast film noir', BBC News 23 February 2007

- ^ 'Filming locations for Odd Man Out The Internet Movie Database

- ^ Fowler, Roy; Haines, Taffy (15 May 1990). "Interview with Sidney Gilliat" (PDF). British Entertainment History Project. p. 124.

- ^ a b Connelly 2012, p. 148.

- ^ Rogers, Steve. Soldier in the Snow: A Look at the Making of Odd Man Out, Its Key Players and Critical Recognition. (Network, 2006).

- ^ Moss 1987, p. 69.

- ^ "Monthly Film Bulletin review". screenonline.org.uk.

- ^ "JAMES MASON 1947 FILM FAVOURITE". The Irish Times. Dublin, Ireland. 2 January 1948. p. 7.

- ^ Moss 1987, p. 146.

- ^ a b Cronin 2005, pp. 159, 189.

- ^ Vidal, Gore. "Screening History – The William Massey Sr. Lectures in the History of American Civilisation 1991".(Harvard University Press).

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (1 September 2006). "Odd Man Out". the Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (10 February 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 38. Retrieved 2 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

edit- Connelly, Mark (2012). The IRA on Film and Television : a History. Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Publishers. ISBN 9780786489619.

- Cronin, Paul, ed. (2005). Roman Polanski: Interviews. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-800-5.

- Moss, Robert F. (1987). The Films of Carol Reed. New York City, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05984-8.

- Jerry Vermilye The Great British Films, Citadel Press, 1978, pp. 106–109 ISBN 0-8065-0661-X

External links

edit- Odd Man Out at IMDb

- Odd Man Out at AllMovie

- Odd Man Out at the TCM Movie Database

- Odd Man Out at Rotten Tomatoes

- Odd Man Out at BFI Screenonline

- Odd Man Out radio adaptation at Suspense on 11 February 1952 with James Mason and Pamela Kellino

- Odd Man Out: Death and the City an essay by Imogen Sara Smith at the Criterion Collection