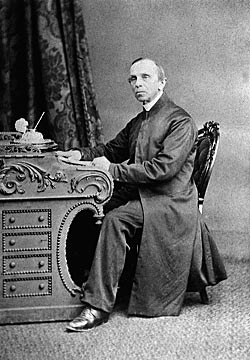

Vladimir Pecherin

Vladimir Sergeyvich Pecherin (Владимир Сергеевич Печерин) (27 June 1807 – 28 April 1885), was a Russian nihilist, Romantic poet, and Classicist, who later became a Roman Catholic priest in 19th-century Ireland.

A member of the hereditary Russian nobility from Odessa, Pecherin grew up witnessing his father regularly beating both the servants and his own mother. After he was an adult, he briefly served as a Professor of Classics at the University of Moscow, but left both his faculty position and the Russian Empire to become a dissident intellectual who rejected and denounced both Christianity and Tsarism.[1]

After several years of living in Europe, Pecherin shocked everyone who knew him by converting from Atheism to the Roman Catholic Church. He eventually was ordained to the priesthood and spent the remainder of his life ministering to the poorest of the poor in the tenement slums and hospitals of Dublin, Ireland.

As a former Westernizer, Fr. Pecherin's autobiographical notes and in his letters to other Russians provide a historical context to the ideological evolution of the Russian intelligentsia during the 1860s and 1870s. Pecherin's writings present the Russian Zeitgeist[2] of the period artistically. In his native Russia, where Pecherin, despite his later religious conversion, remained, "a powerful symbol of anti-Russian sentiment and religious apostasy",[3] he is believed to have inspired many characters in Russian literature, particularly in the novels of Mikhail Lermontov and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Early years

[edit]Pecherin was born in the town of Velyka Dymerka in the Russian Empire (modern-day Ukraine) on 27 June 1807.[4] He was raised in the Russian Orthodox Church and,[5] as a child, was presented to the governor general and founder of Odessa, French Royalist émigré Armand Emmanuel de Vignerot du Plessis, 5th Duke of Richelieu.

Like many other Russian aristocrats of his generation, Pechorin was educated on his ancestral estate by a foreign-born tutor, who instilled in him an enthusiasm for the ideas of the French Age of Enlightenment and German Romanticism, "which contrasted dramatically with the despotic atmosphere of his family and of Russian society in general."[6]

When Pecherin was still a very young child, the family doctor predicted, "This child will become either a poet or an actor." Pecherin later recalled about this prophecy, "Indeed I was a poet, not in verse, but in real life. Under the influence of lofty inspiration I have conceived and constructed the long poem of my life and, according to all the rules of art, I have maintained its complete unity."[7]

Pecherin was attracted to the moral and religious ideology of Utopian socialism. He entered Moscow University, as a student of Classical linguistics, and he wrote manuscripts of poetry that circulated among his university companions. Pecherin was sent abroad for two years on a government scholarship to complete his education.

In 1835, after returning to Moscow University from his travels, even before completing his degree, Pecherin was appointed as Professor of the Greek Language and the Classics. After one term, in 1836, he left Russia to pursue Russian nihilism in Europe. In a letter explaining to the authorities, Pecherin stated that he would never return to a country among whose inhabitants it was impossible to find the imprint of their Creator. He is considered by some to have been the first Russian political emigrant.

Self-exile

[edit]In 1840, after four years as part of the literary bohemia of Europe and at times being reduced to complete poverty, Pecherin unexpectedly converted to Roman Catholicism and became a member of the Redemptorists whose mission was to work among the poorest of the poor. He lived in a monastery in Clapham, near London and later in Ireland, where his skills as an orator attracted large audiences and made Pecherin's sermons very popular.[8]

In 1855, he was the last person to be prosecuted for blasphemy in Ireland.[9] The trial, which was a major public event, took place at Kingstown. Fr. Pecherin, who had been spearheading a campaign against immoral literature, stood accused of burning copies of the Protestant King James Bible in the same bonfire with immoral and pornographic literature upon Guy Fawkes Day. Despite many witnesses, the jury returned a verdict of not proven. Fr. Pecherin's acquittal was raucously celebrated by the Catholic population of Dublin.

In 1856, Fr. John Henry Newman invited Pecherin to preach a St Patrick's Day sermon in the chapel of the newly founded University College Dublin. An attendee later recalled, "One year... the famous Russian missionary, Father Petcherine, appeared in the pulpit and preached the panegyric of the Saint in a truly wonderful address. This foreigner, with a command in English which the most practiced orators might have envied, not only analyzed the character and motives of St. Patrick, and described his career with extraordinary and spirit-stirring power, but also evinced a pathetic sympathy - the interest of the heart - with the woeful history of the people whose cause for religious sake he had made his own, which moved not a few of those present to tears."[10]

Later life

[edit]Like many other Russian intellectuals of his generation, Pecherin was very enthusiastic and hopeful about the political reforms instituted in the Russian Empire following the coronation of Tsar Alexander II, and most particularly by the 1861 abolition of serfdom in Russia.[11]

In 1862, after 20 years of service as a missionary, Pecherin was permitted leave the Redemptorists at his own request. To save him from destitution, Pecherin was assigned by the Archbishop of Dublin, Cardinal Paul Cullen, who respected Pecherin despite their differing views about the Syllabus of Errors, as chaplain at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital. There, as a virtual hermit, Pecherin spent the last 23 years of his life.[12]

In 1863, the extreme Slavophile Moscow Gazette argued that Pecherin's return to Russia might be welcome, but only if he would agree to facilitate better relations between the Government and the Catholic clergy, who were alleged to have singlehandedly instigated the recent nationalist January Uprising against Tsarist rule in Congress Poland. In reality, Pecherin's conversion to Catholicism had not altered his support for the decolonisation of the Russian Empire. He accordingly supported both self determination and derussification for the Polish people and "found the idea of being a loyal subject of the Russian Tsar preposterous. However, he also wanted to affirm his loyalty to the values that were dear to his generation and to present his own version of his life story." The incident accordingly inspired him to write his memoirs, Apologia pro vita mea (Notes from Beyond the Tomb).[13]

In response, Pecherin reached out to his former St Petersburg University friend Feodor Chizhov and began making arrangements to write and publish his memoirs.[14]

As his explanation why, Pecherin wrote, "I happen to lead two lives: one here, the other in Russia. I cannot get rid of Russia. I belong to her with the very essence of my being. It is thirty years since I have settled here - yet, I'm still a stranger. My spirit and my dreams wander not hither - at least, not in the setting to which I was chained by fatal necessity. I don't care if anyone remembers me here when I die, but Russia is another matter. Oh, how much, how much I wish to leave some memory of myself on Russian soil! At least one printed page, witnessing the existence of a certain Vladimir Sergeev Pecherin. That page would be my gravestone saying: 'Here lie the heart and mind of V. Pecherin.'"[15]

Despite his self-deprecating humour alleging a lack of ability in the Russian language, Pecherin skillfully emulated the prose style of other writers. As he described the era of his childhood, he expressed himself in the historical prose of Alexander Pushkin. As he described his early adulthood, he did so in the writing styles of Ivan Turgenev and Nikolai Karamzin. Later events were described in an idiom similar to Fyodor Dostoevsky and even Anton Chekhov, who was still a schoolboy.[16]

During his time in Dublin, Pecherin had remained harshly critical of Tsarism, but had also grown to increasingly oppose certain policies of Pope Pius IX. During an era of increasingly bitter struggle between Liberal Catholicism, Secularism, and Caesaropapism on the one hand with Traditionalist Catholicism and Ultramontanism on the other, the Pope's crusade against certain elements of Classical Liberalism and the natural sciences struck Pecherin as excessive and left him feeling deeply disillusioned. These are the reasons for the bitterness sometimes expressed in his memoirs; in all which he, "described his years in the Redemptorist Order as spiritual slumber and his entire Catholic experience as a fatal error of judgment."[17]

There were other reasons for this, however, according to Pecherin scholar Natalia Pervukhina-Kamyshnikova, "Aware of the incomprehensibility of his conversion and his readers' insatiable curiosity about his motivation, he tried to minimize the significance of his Catholic experience in their eyes. That accounts for the playful, almost frivolous tone in his description of the most important step he took in life. He puts the blame for his decision on the aesthetic enchantment he found in Lamennais and George Sand. He explains his conversion as inspired by visions of a poetic wilderness and by literary images that drew him inexorably to monastic life."[18]

After carefully editing excerpts from Pecherin's many letters to him between 1865 and 1877 into a book length memoir, Chizhov fought to get the volume published. Despite Chizhov's best efforts and the limited relaxation of censorship in the Russian Empire under Tsar Alexander, however, "political considerations" still prevented the publication of Pecherin's memoirs. Chizhov died in 1877, without having seen them appear in print.[19]

Pecherin died in Dublin on 17/29 April 1885. His obituary in the Freeman's Journal commented, "Father Pecherin will be deeply regretted for his great piety, unassuming demeanor, gentleness of disposition, and charity." He was buried first at Glasnevin Cemetery and, despite his departure from the Order, on 1 May 1991, Pecherin's body was re-exhumed and reburied in the Redemptorist plot at Deansgrange Cemetery in Dun Laoghaire.[20]

Pecherin's memoirs remained unpublished in Russia until Mikhail Gershenzon began publishing limited excerpts in 1910. The first complete edition was finally released in a limited run in 1932.[21]

Quotes

[edit]- "How sweet it is to hate one's fatherland and eagerly anticipate its annihilation, and to see in the destruction of one's fatherland the dawn of worldwide rebirth."[22]

In popular culture

[edit]- According to Pecherin scholar Natalia Pervukhina-Kamyshnikova, Mikhail Lermontov is believed to have named the Byronic hero of his 1840 novel A Hero of Our Time "Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin" in a deliberate reference to Vladimir Pecherin.[23]

- According to Pecherin scholar Natalia Pervukhina-Kamyshnikova, Fyodor Dostoevsky, as a passionate believer in Tsarism, Russian Orthodoxy, Caesaropapism, Slavophilism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Catholicism, considered Pecherin, "to be the emblematic figure of a Westerniser, a person who had lost his identity and human worth by severing his Russian roots."[24] It is accordingly believed that Dostoevsky's anti-materialist "one secluded thinker" in The Idiot is an allusion to Pecherin.[25] The early life and Romantic poetry of Stepan Trofimovoch Verkhovensky in Dostoevsky's The Possessed are also a deliberate satire of Pecherin.[26][27] Furthermore, Stepan Trofimovich's "wicked parody" in the same novel of Pecherin's The Triumph of Death, is now "better known than the original poem." The Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov, "uses arguments that Dostoevsky attributed to Catholics like Pecherin."[28]

- In the movie The Russia House, starring Sean Connery, Klaus Maria Brandauer's character "Dante," a Russian scientist, quotes Pecherin.

References

[edit]- ^ UCD PRESS, The First Russian Political Émigré

- ^ Partial Answers, Journal of Literature and The History of Ideas, Volume 2, Number 1 (June 2004)

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. ix.

- ^ Peoples.ru

- ^ Taghmon Historical Society Vol. 4

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. ix.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xi.

- ^ "Russian to judgment – Frank McNally on Fr Vladimir Pecherin and the Kingstown blasphemy trial of 1855". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ "Russian to judgment – Frank McNally on Fr Vladimir Pecherin and the Kingstown blasphemy trial of 1855". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiii.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiii.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiii.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xv.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xv-xvi.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xv-xvi.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xix.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiii, xvii.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xviii.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiv.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xiv.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. xvi.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. x.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. x.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. x.

- ^ Dostoevsky: The Miraculous Years, 1865-1871 by Joseph Frank, p. 201.

- ^ "Russian to judgment – Frank McNally on Fr Vladimir Pecherin and the Kingstown blasphemy trial of 1855". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. x.

- ^ Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press. p. x.

Further reading

[edit]- Vladimir Pecherin (2008), The First Russian Political Émigré: Notes from Beyond the Grave, or Apologia Pro Vita Mea, University College Dublin Press.

- 1807 births

- 1885 deaths

- 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century poets

- 19th-century Roman Catholic priests from the Russian Empire

- Anti-Protestantism

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Eastern Orthodoxy

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United Kingdom

- Former Russian Orthodox Christians

- People from Brovary Raion

- People from Ostyorsky Uyezd

- Redemptorists

- Romantic poets

- Russians in Ukraine

- Russian male poets

- Russian Catholic poets

- Westernizers