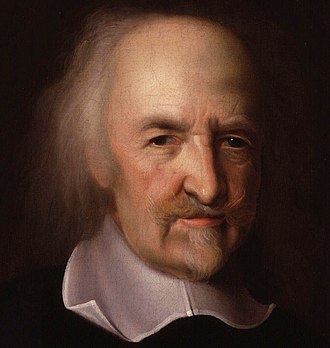

Hobbes's moral and political philosophy

Thomas Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy is constructed around the basic premise of social and political order, explaining how humans should live in peace under a sovereign power so as to avoid conflict within the ‘state of nature’.[1] Hobbes’s moral philosophy and political philosophy are intertwined; his moral thought is based around ideas of human nature, which determine the interactions that make up his political philosophy.[2] Hobbes’s moral philosophy therefore provides justification for, and informs, the theories of sovereignty and the state of nature that underpin his political philosophy.[2]

In utilising methods of deductive reasoning and motion science, Hobbes examines human emotion, reason and knowledge to construct his ideas of human nature (moral philosophy).[3] This methodology critically influences his politics, determining the interactions of conflict (in the state of nature) which necessitate the creation of a politically authoritative state to ensure the maintenance of peace and cooperation.[4] This method is used and developed in works such as The Elements of Law (1640), De Cive (1642), Leviathan (1651) and Behemoth (1681).[5]

Methodology

[edit]In developing his moral and political philosophy, Hobbes assumes the methodological approach of deductive reasoning, combining mathematics and the mechanics of science to formulate his ideas on human nature.[1] Hobbes was critical of the assumptions of scholastic philosophers, whose evidence for human nature was based upon Aristotelian metaphysics and Cartesian observation, as opposed to reasoning and definition.[5] Though Hobbes did not fully reject the value of observational or ‘prudential’ knowledge, he dismissed the view that this was at all scientific or philosophical in nature.[5] To Hobbes, this type of knowledge was based on subjective and diverse experience, and was therefore capable of producing only speculative assumptions.[5] This view predetermined Hobbes’s method of deductive reasoning, which involved the application of geometry, Galilean scientific concepts and definition.[5] This scientific method stresses the importance of first establishing well-defined principles of human nature (moral philosophy) and ‘deducing’ aspects of political life from this.[1] Hobbes first used the mechanics of motion to define principles of human perception, behaviour and reasoning, which were then used to draw the conclusions of his political philosophy (sovereignty, state of nature).[1] In rejecting what he believed were ‘conjectures’ relating to intangible or supernatural objects or realities, Hobbes’s philosophy is drawn from material and physical reality and experience.[3] Höffe explains how Hobbes applied this method to construct his political theory of sovereignty:

“…the combination of mathematics and mechanics, is not sufficient on its own… the combination of mathematics and mechanics leads to the metaphor of the state as an “artificial” human being, which is comparable to a machine constructed out of natural human beings; (3) the resoluto-compositive [the recourse to absolutely first principles or elements] method defines and clarifies the nature of this construction: the artificial human being is decomposed into its smallest constituent parts and then recomposed, i.e., constructed, out of these parts".[3]

Hobbes’s moral principles thus provide the ultimate basis for his political philosophy, defining and clarifying how an “artificial” sovereign authority may come into existence.[3]

Moral philosophy

[edit]Hobbes’s moral philosophy is the fundamental starting point from which his political philosophy is developed. This moral philosophy outlines a general conceptual framework on human nature which is rigorously developed in The Elements of Law, De Cive and Leviathan.[5] These works examine how the laws of motion influence human perception, behaviour and action, which then determine how individuals interact.[5] The Elements of Law provides insight into Hobbes’s moral philosophy through ideas of sensation, pleasure, passion, pain, memory and reason.[6] This is expanded upon in De Cive: “… human nature… comprising the faculties of body and mind; . . . Physical force, Experience Reason and Passion".[6] Hobbes believes that as sensory organs process the movements of external stimuli, a range of different mental experiences take place, which in turn dictate human behaviour.[7] What emerged from this idea of motion was the view that humans are naturally drawn towards, or desire, things that benefit their overall wellbeing; things that are “good” for them.[7] These are called “appetites”, and what differentiates the human ‘appetite’ from that of animals is reason.[4] Reason, or “ratiocination”, as used by Hobbes, was not defined in the traditional sense as an innate capability tied to notions of natural law, but as an activity that involved coming to a judgement via the process of logic.[6] Humans, as noted in Leviathan, have “…knowledge of the consequences of one affirmation to another”.[6] Individuals will desire and select whatever ‘thing’ brings them the most “good”.[7] This process of thinking is a consequence of motion and mechanics more than a conscious exercise of choice.[7] Ratiocination leads individuals to uncover the Laws of Nature, which Hobbes deems “the true moral philosophy”.[2]

Hobbes’s understanding of human nature establishes the foundations for his political philosophy by explaining the essence of conflict (in the state of nature) and cooperation (in a commonwealth).[6] Because human beings will always pursue what is ‘good’ for them, this philosophy asserts that individuals share overarching desires or goals, such as security and safety (especially from death).[6] This is the point in which Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy intersect: in “our shared conception of ourselves as rational agents”.[2] It is rational to “pursue the necessary means to our dominant shared ends”, in which case the “necessary means” is submission to a sovereign authority.[5] By establishing morality as a force which directs individuals towards their shared desires and goals of, for example, peace and security, and the means to achieve these goals is through the creation of a state, Hobbes grounds his political philosophy in his moral thought.[5] This approach to moral philosophy is executed by Hobbes through discussion of a range of interrelated moral concepts: “good, evil, rights, obligation, justice, contract, covenant and natural law”.[5]

Moral concepts

[edit]Obligation

[edit]Hobbes’s concept of moral obligation stems from the assumption that humans have a fundamental obligation to follow the laws of nature and all obligations stem from nature.[8] His reasoning for this is premised upon the beliefs of natural law; that the moral standards or reasoning that govern behaviour can be drawn from eternal truths regarding human nature and the world.[1] Hobbes believes that the morals derived from natural law, however, do not permit individuals to challenge the laws of the sovereign; law of the commonwealth supersedes natural law, and obeying the laws of nature does not make you exempt from disobeying those of the government.[1]

Hobbes’s concept of moral obligation thus intertwines with the concept of political obligation. This underpins much of Hobbes’s political philosophy, stating that humans have a political obligation or ‘duty’ to prevent the creation of a state of nature.[9] Humans have a political obligation to obey a sovereign power, and once they have renounced part of their natural rights to this power (theory of sovereignty), they have a duty to uphold the ‘social contract’ they have entered into.[9]

Political philosophy

[edit]

The main aspects of Hobbes’s political philosophy revolve around the contrasting relationship between the state of nature (a state of war) and the State itself as one of peace and cooperation. This philosophy is determined by, and implied in, his method of deduction.[4] The trajectory of individual desire and will outlined in his moral philosophy is a decisive factor contributing to the formulation of his idea of the State.[4]

Hobbes outlined four key principles of purpose in his philosophical literature:

- Welfare of the general public.[3]

- State of well-being and satisfaction with life.[3]

- The pursuit of justice.[3]

- The pursuit of peace (to avoid the ‘state of war’).[3]

These concepts are mutually reinforcing and feature across his most prominent works. For example, in The Elements of Law, Hobbes claims that the benefits given to the general public under a commonwealth are “incomparable”.[3] This overlaps with his discussion of justice in the same text, which is used in a political context.[3] Leviathan details all four principles but focuses on the pursuit of peace, which Hobbes aligns with the first principle of welfare and public good.[3] Where a state of peace (4) and justice (3), and the overall welfare of the general public (1), manifest under a commonwealth (stemming from ‘commonweal’: the general good of the public), a state of well-being and overall satisfaction (2) may be secured.[3] Only under the commonwealth (as opposed to a state of nature and war) can peace, and “the notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice”, exist indefinitely.[3] This is expanded upon again in The Elements of Law, which posits that humans by nature are inclined towards conflict, and therefore need a State to institute peace and protect individuals against the threats of self-preservation which flourish in a state of nature.[9] De Cive also builds on the relationship between these principles, where Hobbes’s claim to show individuals the “highway to peace” affirms his notion that humans should pursue peace, and therefore justice, in the form of a commonwealth.[3] It is in the interest of humans to pursue peace, who have a fundamental obligation to follow the Laws of Nature.[3]

A sovereign power or authority figure - a Leviathan - is needed to translate these Laws of Nature in a “binding and authoritative fashion”.[3] The notion that individuals require a “visible power to keep them in awe” - to maintain peace and safety through enforcement of law - underpins Hobbes’s theory of sovereignty, which proposes that a sovereign ruler (with authority to govern the people) is fundamental to any type of commonwealth.[10] Therefore, the overarching concern of Hobbes’s political philosophy remains the capacity of the government to maintain peace, protection, justice and wellbeing in a manner that ensures the continuation of society and civil life.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Williams, Garrath. "Thomas Hobbes: Moral and Political Philosophy". Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c d e Lloyd, Sharon A. (2009). Morality in the Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes: Cases in the Law of Nature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4-5. ISBN 9780521861670.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Höffe, Otfried (2015). Thomas Hobbes. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 2–60.

- ^ a b c d Strauss, Leo (1963). The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2-9. ISBN 9780226776965.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kavka, Gregory S. (1986). Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 7–292.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bunce, Robin E. R. (2009). Thomas Hobbes. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. pp. 20–32.

- ^ a b c d Finn, Stephen. "Thomas Hobbes: Methodology". Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Gauthier, David P. (1979). The Logic of Leviathan: The Moral and Political Theory of Thomas Hobbes. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 40.

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Sharon A. "Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez (2009). Hobbes and the Law of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 66.