Story and photos by Graham Gauld

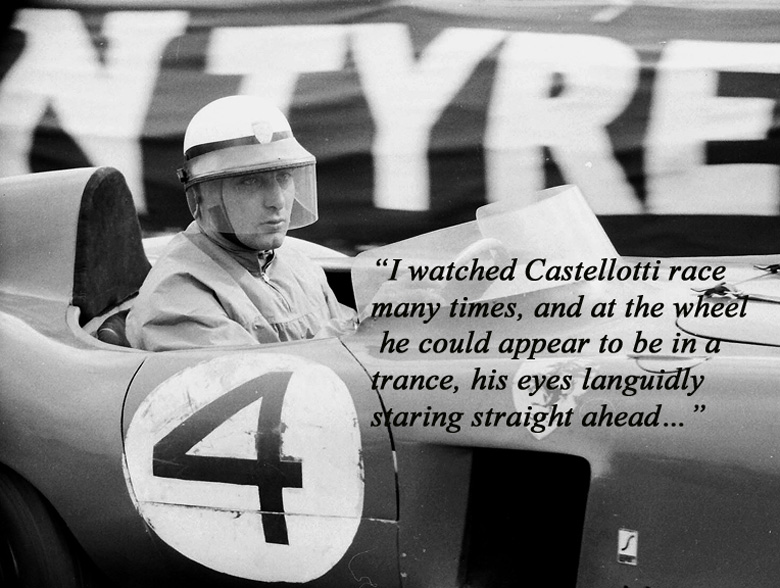

From the VeloceToday archives, 2019. Lead image: A close-up of Castellotti at Dundrod in 1955, concentrating hard while accelerating away from the hairpin in the Ferrari 850 Monza.

There are times when we can all be rather pretentious. I fell into that trap thirty years ago when I had the idea of writing a subjective book on the psychology of the racing driver. I have always had an interest in the variety of people who come into motor sport and what makes them tick. I had read a lot about psychology in general, then dropped the idea when I realized what a fool I might have made of myself. However, if Central Casting in Hollywood were ever asked for a “racing driver type” back in the 1950s, they would have to have chosen Eugenio Castellotti.

I watched Castellotti race many times and at the wheel he could appear to be in a trance, his eyes languidly staring straight ahead, but his body language all action. It was his custom to ‘tiger’ as soon as the flag came down, often outrunning many of the accepted champions. But he tended to be hard on the car and Castellotti was usually one of the first to change tires.

Eugenio Castellotti at the wheel of the Lancia-Ferrari at the 1956 British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

Eugenio Castellotti was born in Lodi in 1930 and was rich, dashing, and handsome. Though he came from a titled Italian family, they did not support his passion for motor racing. However, at the tender age of 20 he bought a brand new Ferrari 166 barchetta (0058M) from a dealer in Genoa just in time to compete in the Tour of Tuscany. (It has been the suggestion that in fact he did not actually buy the car until after the Tuscan event and that the Genoa dealer Sig. Braida was the entrant and that Castellotti bought the car later.)

His next event was the Mille Miglia in 1950, his car being entered by Scuderia Guastella which continued to enter him in events until August 1952, when he won the Circuito di Senigallia in his two-year-old 166 barchetta. Scuderia Guastella entered Castellotti for the Monaco Sports Car race in 1952 and he finished second to teammate Vittorio Marzotto but this time in a 225S ( Chassis 0166ED).

Eugenio Castellotti at the wheel of the Lancia D24 sports car in the 1954 Tourist Trophy race at Dundrod in Ireland.

However, it was not Ferrari who approached Castellotti to be a factory driver in 1953, but Ferrari’s great rivals Lancia who entered him for the Pan American Road race, and he repaid them by finishing third in a Lancia D23.

The following year he was one of a stellar team of Lancia drivers (Fangio, Taruffi, Ascari, and Villoresi) in the factory D24s. It was driving a D24 at the Dundrod Tourist Trophy race of ’54 that I first saw Castellotti race. He was very much the junior driver in the team, and so was entered as reserve to drive each of the four factory cars in the race. The best placed Lancia finished 6th.

During 1954 Lancia had also developed a Grand Prix car which was given to Alberto Ascari for the Spanish Grand Prix that year, but for 1955 they mounted a major effort with three factory Lancias for Ascari, Villoresi, and Castellotti as drivers. For Castellotti success came early with a strong second place in the Monaco Grand Prix, but in the same race he had also seen his close friend and mentor, Ascari, go off the road and into the harbor where he was rescued by frogmen. Relieved, that Alberto was not seriously injured, Castellotti and Ascari returned to Milan.

Four days later Castellotti was out testing the unpainted Ferrari 750 Monza at Monza before the Supercortemaggiore race when Ascari turned up to watch. Eugenio was pleased to see Ascari, who asked whether he could have a few laps in the car. Castellotti loaned Ascari his helmet; three laps later Ascari lay dead on the track at the fast Vialone Curve at the back of the circuit. He had been thrown out and killed. Castellotti was grief stricken, and at the huge funeral that took place in Milan a few days later, Castellotti was one of the pall bearers who carried Ascari’s coffin.

Gianni Lancia had decided to wind up the Grand Prix program after the Belgian Grand Prix and the cars were transferred to Scuderia Ferrari. Castellotti now had his first factory Grand Prix drive for the Scuderia at the Dutch Grand Prix where he finished fifth. He continued to race for Ferrari until 1957.

Meanwhile a new young Italian driver was challenging Castellotti. Luigi Musso and Castellotti were to become great rivals, particularly as both raced for Scuderia Ferrari.

Though Musso was married, Castellotti was still attracting lots of girlfriends but during 1956 one of them became very special; Delia Scala, the Italian film actress. Their relationship blossomed during 1956 and, as was well known, Enzo Ferrari was not sympathetic to the social lives of his drivers – particularly if women were involved. In Italy, however, the handsome racing driver who raced for Ferrari and the beautiful film actress was a story made in heaven.

At Dundrod in 1955, Castellotti leads the DB-Panhard HBR of Claude Storez and the Cooper-Jaguar of Peter Whitehead.

For the 1957 season Enzo Ferrari decided to retain the Lancia V8 engines but put them into a new Formula 1 car called the 801 with a completely new chassis. Castellotti was one of the team of drivers who drove it in Argentina, but he retired when a hub overheated and a wheel came off. He then went off on holiday with Delia Scala, only to receive a telephone call from Enzo Ferrari, who knew that Castellotti was not far away in Florence, ordering him back to Modena to test some other modifications to the 801 at the Autodrome.

He got up at dawn and drove over the Raticosa and Futa passes to Bologna and thence to Modena. When he arrived at the circuit the car was already there. It turned out that Jean Behra had broken the lap record at Modena Autodrome testing a 250F Maserati and Ferrari felt that the lap record was traditionally his, hence the test session and Enzo Ferrari was on hand to watch. Castellotti warmed up the car and then set off for a quick lap, only to misjudge the first chicane which at the time was lined with small bushes and a solid grandstand. The Lancia-Ferrari bounced off one of the red and white kerb stones and Castellotti was thrown out against a concrete pillar and killed.

Castellotti trying hard with the Ferrari 625 in the 1955 British Grand Prix at Aintree ahead of teammate Maurice Trintignant.

The Italians they had lost a hero, and the press laid part of the blame on Ferrari for breaking up Castellotti’s holiday. Ferrari countered by saying that Castellotti had been in a bad mood (understandable) and inferred that Eugenio had let a woman influence him so much.

Only a few short weeks later came the Mille Miglia, where Castellotti’s seat was given to the veteran Piero Taruffi. Taruffi followed in Castellotti’s footsteps and won the Mille Miglia for Ferrari; but at what cost? Alfonso de Portago and Ed Nelson in a sister car were involved in an accident that claimed the lives of a lot of spectators, and the Mille Miglia as a completely free and open road race on public roads, ended once and for all.

History has a habit of remembering only the winners. Eugenio Castellotti never won a single Grand Prix, but was the archetypal Grand Prix driver who stood on the fringe of greatness. Through his career his impetuousness too often caught him out; it was probably so at Modena that day, March 14, 1957, when he died.

Has anyone ever complied an acute account of all the drivers killed trying to satisfy the man in the dark glasses ?