Parts of this article (those related to Population) need to be updated. (August 2023) |

Teddington is an affluent suburb of London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Historically an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex and situated close to the border with Surrey, the district became part of Greater London in 1965. In 2021, The Sunday Times named Teddington as the best place to live in London,[2] and in 2023, the wider borough was ranked first in Rightmove's Happy at Home index, making it the "happiest place to live in Great Britain"; the first time a London borough has taken the top spot.[3][4]

| Teddington | |

|---|---|

| |

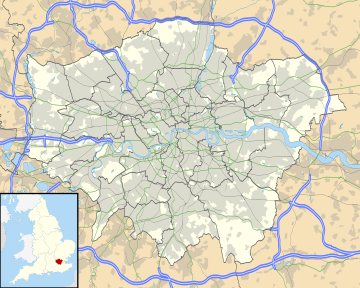

Location within Greater London | |

| Area | 4.27 km2 (1.65 sq mi) |

| Population | 10,562 (2021)[1] |

| • Density | 2,474/km2 (6,410/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ159708 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | TEDDINGTON |

| Postcode district | TW11 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Teddington is situated on a long meandering of the Thames between Hampton Wick and Strawberry Hill, Twickenham. Mostly residential, it stretches from the river to Bushy Park with the commercial focus on the A313 road. At Teddington's centre is the High Street and Broad Street, alongside mid-rise urban developments, containing offices and apartments. There is a suspension bridge over the lowest non-tidal lock on the Thames, Teddington Lock.

Economy

editThe district's commercial focus – containing shops, offices and other facilities – is along the A313, which is named (from west to east): Hampton Road, Broad Street and High Street. Broad Street contains a mixture of chain shops, cafes and supermarkets, alongside independent businesses, while the High Street is composed of nearly all local and independent businesses and restaurants from Teddington and South West London.

There are two clusters of offices on this route; on the edge of Bushy Park the National Physical Laboratory, National Measurement Office and LGC form a scientific centre. Around Teddington station and the town centre are a number of offices in industries such as direct marketing and IT, which include Tearfund and BMT Limited. Several riverside businesses and houses were redeveloped in the last quarter of the 20th century as blocks of riverside flats. Starting in 2016 the riverside site of the former Teddington Studios was redeveloped to provide modern apartment blocks and other smaller houses.[5]

The lowermost lock on the Thames, Teddington Lock, which is just within Ham's boundary, is accessible via the Teddington Lock Footbridges. In 2001 the Royal National Lifeboat Institution opened the Teddington Lifeboat Station, one of four Thames lifeboat stations, below the lock on the Teddington side. The station became operational in January 2002 and is the only volunteer station on the river.

History

editEtymology

editThe place-name ‘Teddington’ is first attested in a Saxon charter of 969, where it appears as ‘Tudintún’ (’The Crawford Collection of Early Charters’, Oxford, 1895). It appears as ‘Tudincgatun’ in the ‘Cartularium Saxonicum’ edited by Birch, published in London from 1895-1893. It is listed as ‘Tudinton’ in the Feet of Fines for 1197. The name means “the tūn [town or settlement] of Tud(d)a’s people”.[6]

Teddington is at the point of the River Thames where tidal flow ceases owing to it containing the 'final lock'. It has been postulated that the name thus derives from "Tide End Town." Such theory featured in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, "The River's Tale", which has the line "At Tide-end-town, which is Teddington." The poem was written to serve as the introduction to a history of England for schoolchildren, written by C.R.L. Fletcher, published by the Clarendon Press in Oxford in July 1911, and by Doubleday Page in New York in September 1911.

Teddington's beginnings

editThere have been isolated findings of flint and bone tools from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in Bushy Park, and some unauthenticated evidence of Roman occupation.[7] However, the first permanent settlement in Teddington was probably in Saxon times. Teddington was not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as it was included under the Hampton entry.

Teddington Manor was first owned by Benedictine monks in Staines, and it is believed they built a chapel dedicated to St. Mary[which one?] on the same site as today's St. Mary's Church. In 971, a charter gave the land in Teddington to the Abbey of Westminster. By the 14th century Teddington had a population of 100–200; most of the land was owned by the Abbot of Westminster and the remainder was rented by tenants who had to work the fields a certain number of days a year.

The Hampton Court gardens were laid out in 1500 in preparation for the planned rebuilding of a 14th-century manor to form Hampton Court Palace in 1521. They were to serve as hunting grounds for Cardinal Wolsey and later Henry VIII and his family. In 1540 some common land of Teddington was enclosed to form Bushy Park, and also used as hunting grounds.

Bushy House was built in 1663. One notable resident was British Prime Minister Lord North, who lived there for over twenty years.[8]

A large minority of the parish lay in largely communal open fields, restricted in the Middle Ages to certain villagers. These were inclosed (privatised) in two phases, in 1800 and 1818.[9][10] Shortly afterwards, the Duke of Clarence lived there with his mistress Dorothy Jordan[11] before he became King William IV, and later with his Queen Consort, Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. The buildings were later used for the National Physical Laboratory.

Economic change

editIn subsequent centuries, Teddington enjoyed a prosperous life due to the proximity of royalty, and by 1800 had grown significantly. But the "Little Ice Age" had made farming much less profitable and residents were forced to find other work. This change resulted in great economic change in the 19th century.

The first major event was the construction of Teddington Lock in 1811 with its weir across the river.[12] This was the first (and now the biggest) of five locks built at the time by the City of London Corporation. In 1889 Teddington Lock Footbridge, consisting of a suspension bridge section and a girder bridge section, was completed, linking Teddington to Ham (then in Surrey, now in London). It was funded by local business and public subscription.

After the railway was built in 1863, easy travel to Twickenham, Richmond, Kingston and London was possible and Teddington experienced a population boom, rising from 1,183 in 1861 to 6,599 in 1881 and 14,037 in 1901.[13]

Many roads and houses were built, continuing into the 20th century, forming the close-knit network of Victorian and Edwardian streets present today. In 1867, a local board was established and an urban district council in 1895.

In 1864 a group of Christians left the Anglican Church of St. Mary's (upset at its high church tendencies) and formed their own independent and Reformed, Protestant-style, congregation at Christ Church. Their original church building stood on what is now Church Road.

The Victorians attempted to build a large church, St. Alban's, based on the Notre Dame de Paris; however, funds ran out and only the nave of what was to be the "Cathedral of the Thames Valley" was completed.[14] In 1993 the temporary wall was replaced with a permanent one as part of a refurbishment that converted St Alban's Church into the Landmark Arts Centre, a venue for concerts and exhibitions.

A new cemetery, Teddington Cemetery, opened at Shacklegate Lane in 1879.[15]

Several schools were built in Teddington in the late 19th century in response to the 1870 Education Act, putting over 2,000 children in schools by 1899, transforming the previously illiterate village.

20th century

editOn 26 April 1913 a train was almost destroyed in Teddington after an arson attack by suffragettes.[16]

Great change took place around the turn of the 20th century in Teddington. Many new establishments were springing up, including Sims opticians. In 1902 the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), the national measurement standards laboratory for the United Kingdom, and the largest applied physics organisation in the UK, started in Bushy House (primarily working in industry and metrology and where the first accurate atomic clock was built) and the Teddington Carnegie Library was built in 1906. Electricity was also now supplied to Teddington, allowing for more development.

Until this point, the only hospital had been the very small cottage hospital, but it could not accommodate the growing population, especially during the First World War. Money was raised over the next decade to build Teddington Memorial Hospital[17] in 1929.

By the beginning of the Second World War, by far the greatest source of employment in Teddington was in the NPL.[citation needed] Its main focus in the war was military research and its most famous invention, the "bouncing bomb", was developed. During the war General Dwight D. Eisenhower planned the D-Day landings at his Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) at Camp Griffiss in Bushy Park.

The "towpath murders" took place across the river in 1953. On 1 June, Barbara Songhurst was discovered floating in the River Thames, having been stabbed four times. Her friend Christine Reed, then missing, was found dead on 6 June. On 28 June, Alfred Whiteway was arrested for their murder and the sexual assault of three other women that same year. Whiteway was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 22 November 1953. Whiteway and the girls were all from Teddington. The case was described as "one of Scotland Yard's most notable triumphs in a century".[18]

Teddington Studios, a digital widescreen television studio complex and one of the former homes of Thames Television, opened in 1958 on the site of Weir House. The studios were redeveloped in 2016 into luxury housing, though the old lock keepers cottage that predated the studios, known as Weir Cottage, was preserved.

Most major rebuilding from bomb damage in World War II was completed by 1960. Chain stores began to open up, including Tesco and Sweatshop in 1971.

The Teddington Society

editThe Teddington Society, formed in 1973 by local residents, seeks to preserve the character of Teddington and to support local community projects.[19]

Education

editThe education authority for Teddington is Richmond upon Thames London Borough Council.

Primary schools in Teddington include Collis Primary School (Fairfax Road), St Mary's & St Peter's Primary School (Church Road), Sacred Heart RC School (St Marks Road) and Stanley Juniors and Infants (Strathmore Road).[20] Secondary schools include Teddington School.[21]

St Mary's & St Peter's Primary School was originally founded by Dorothy Bridgeman (d. 1697), widow of Sir Orlando Bridgeman, who left £40 to buy land in trust for educating poor children. In 1832, the foundation opened a boys' school, Teddington Public School, under the patronage of Queen Adelaide. Its buildings now house the primary school.[22]

Leisure

editThe Landmark Arts Centre, an independent charity, delivers a wide-ranging arts and education programme for the local and wider community. Its activities include arts classes, concerts and exhibitions.[23]

Sport

edit- Teddington Cricket Club was formed in the late 19th century, based at Bushy Park.[24]

- Teddington Hockey Club was formed in 1871, and compete in the Men's England Hockey League, the Women's England Hockey League and the London Hockey League.[25] The club was involved in the development of modern day hockey rules, including the introduction of the striking circle and the "sticks" rules.[26][27]

- Kingston Royals Dragon Boat Racing Club

- NPL Sports Club

- Royal Canoe Club, the oldest canoe club in the world

- The Skiff Club, the oldest skiff club in the world, also competes at punting under TPC rules.

- Teddington Athletic F.C.[28]

- Hearts of Teddlothian F.C.[29]

- Teddington Rugby Football Club[30]

- Teddington Lawn Tennis Club[31]

- Walbrook Rowing Club, also known as Teddington Rowing Club

- Weirside Rangers AFC play at the Broom Road site; they have a clubhouse overlooking Teddington Lock.[32]

- Park Lane Stables a Riding for the Disabled Association equine facility

Transport

editRail

editTeddington station is at the centre of the town, and the closest railway station. Additionally, Hampton Wick station is located to the south, Strawberry Hill station to the north, and Fulwell station to the west; all can be reached by London buses from Broad Street.

Teddington railway station, served by South Western Railway trains, is on the electrified Kingston Loop Line close to the junction of the Shepperton Branch Line. Trains run to London Waterloo in two directions around a circular loop: one way via Kingston upon Thames and Wimbledon every 15 minutes, the other via Richmond and Putney every 30 minutes. Trains also run to Shepperton every 30 minutes.

Currently paused, the Crossrail 2 project was planned to run through Teddington Station. Upgrading the existing lines on the Wimbledon section of the South West London network, TfL projected an increase in service up to 10-12 trains an hour to Central London, from a 2015 average of 6.[33]

Buses

editTeddington is served by London Buses services to other London locations, including Heathrow Airport, Hounslow Central, West Croydon and Castelnau. Routes 33, 281, 285, 481, 681, R68 and Superloop SL7 serve the town centre, and all seven connect the town with either Twickenham or Kingston upon Thames.[34]

Geography

editDemography and housing

edit| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ward) | 339 | 972 | 1,217 | 2,065 | 1 | 22 |

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ward) | 10,330 | 4,853 | 31 | 35 | 427 |

Places of worship

edit- St Mary with St Alban Church of England parish church, built circa 1400. St Mary's is the original church; St Alban's, across the road, is now the Landmark Arts Centre

- Teddington Baptist Church – evangelical Baptist church

- Sacred Heart Church, Teddington – Roman Catholic church designed by John Kelly, opened in 1893

- St Mark's, Teddington – Church of England

- Teddington Methodist Church

- Christ Church, Teddington – an independent congregation worshipping in Church of England style

- St Peter & St Paul, Teddington – Church of England

Notable residents

editOnly notable people with entries on Wikipedia have been included. Their birth or residence has been verified by citations.

Living people

edit- Julian Clary, comedian, author, actor and LGBTQIA+ activist, grew up in Teddington.[35]

- Mo Farah, Olympian long-distance runner, has a home in Teddington,[36] and the post box on Broad Street was painted gold in 2012 to celebrate one of his two gold medals in the Olympic Games of that year.

- Andrew Gilligan, journalist and policy adviser, was born in Teddington.[37]

- Viv Groskop, journalist, writer and comedian, lives in Teddington.[38]

- Keira Knightley, actress, grew up in Teddington.[39]

- Jed Mercurio, creator of Line of Duty, lives in Teddington.[40]

Historical figures

editPhotograph by Allan Warren

- The Dowager Queen Adelaide (1792–1849), widow of William IV, spent her last years (1837–1849) at Bushy House, Teddington.[41]

- Luffman Atterbury (1740–1796), composer and builder, lived at a house now known as Clarence House, between Middle Lane and Park Lane facing Park Road, from 1780 until 1790.[42]

- Sir Noël Coward (1899–1973), actor, playwright and songwriter, was born at 131 Waldegrave Road, Teddington.[43][44] There is a bust of Coward, sculpted by Avril Vellacott,[45] in Teddington Library, which is only a short distance away.[46]

- Dorothy Edwards (1914–1982), children's author, was born in Teddington.[47][48]

- Stephen Hales (1677–1761), clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields.[49]

- Benny Hill (1924–1992), comedian, actor, singer and writer, lived and died at Flat 7, Fairwater House, 34 Twickenham Road, Teddington.[50]

- Prince Louis, Duke of Nemours (1814–1896), lived at Bushy House.[51]

- Eugène Marais (1871–1936), South African lawyer, naturalist, poet and writer, lived in Coleshill Road in Teddington from 1898 to 1902.[52]

- Frederick North, Lord North (1732–1792), British statesman, Prime Minister from 1770 to 1782, lived at Bushy House as his London suburban residence when Ranger of Bushy Park, from 1771 to 1792.[8]

- Norman Selfe (1839–1911), engineer, naval architect, inventor, urban planner and advocate of technical education, was born in Teddington.[53]

- John Thaxter (1927–2012), theatre critic, lived in Teddington.[54]

- Thomas Traherne (1636 or 1637 – 1674), a metaphysical poet, theologian, and writer, died here in 1674.

- Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821-1879), society heiress, who Waldegrave Road is named after.

- John Walter (1738–1812), who founded The Times newspaper, died at The Grove, Teddington.[55]

- Margaret "Peg" Woffington (1720–1760), stage actress, lived in Teddington.[56]

- Mary Woffington (1729–1811), socialite, lived in Teddington.[56]

Notes and references

edit- ^ a b c Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine United Kingdom Census 2011 Office for National Statistics Retrieved 20 December 2013

- ^ "Teddington named best place to live in London 2021". The Sunday Times. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Starkie, Emma (6 December 2023). "Where are the 10 happiest places to live in Great Britain?". Property blog. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Block, India (6 December 2023). "Revealed: the London borough named UK's happiest place to live". Evening Standard. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Buchanan, Clare (26 June 2013). "Media group plots move to Teddington". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, ’The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names’, p.462.

- ^ "Bushy Park". Twickenham Museum. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ a b "The Story of Bushy House". National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Twickenham: Introduction | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- ^ Reynolds, Susan (ed.) (1962) "Twickenham: Introduction", in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3, Shepperton, Staines, Stanwell, Sunbury, Teddington, Heston and Isleworth, Twickenham, Cowley, Cranford, West Drayton, Greenford, Hanwell, Harefield and Harlington London: Victoria County History, pp. 139–147. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Jerrold, Clare A. (1914). The Story of Dorothy Jordan. Eveleigh Nash.

- ^ Thacker, Frederick S. (1968) [1920], The Thames Highway, II: Locks and Weirs (Newton Abbot: David & Charles)

- ^ "Table of population, 1801–1901". British History Online.

- ^ "About the Landmark Arts Centre" (PDF). Landmark Arts Centre. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Teddington Cemetery". Cemeteries. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Buchanan, Clare (20 April 2013). "Teddington suffragette attack remembered 100 years on". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Teddington Memorial Hospital Archived 21 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cullen, Pamela V. A Stranger in Blood: The Case Files on Dr John Bodkin Adams (London: Elliott & Thompson, 2006; ISBN 1-904027-19-9).

- ^ Buchanan, Clare (14 October 2013). "Teddington Society celebrates 40th anniversary, then gets straight back to work". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Collis School, St Marys & St Peters, Sacred Heart RC School, Stanley Juniors Archived 2007-08-16 at the Wayback Machine, Stanley Infants Archived 2007-11-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Teddington School". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "Teddington: Schools Pages 81–82 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3, Shepperton, Staines, Stanwell, Sunbury, Teddington, Heston and Isleworth, Twickenham, Cowley, Cranford, West Drayton, Greenford, Hanwell, Harefield and Harlington. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1962". British History Online.

- ^ "Landmark Arts Centre". Teddington Town. 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Teddington CC". teddington.play-cricket.com.

- ^ "England Hockey - Teddington Hockey Club". Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Teddington Hockey Club | Family Sports Club for Beginners to Elite | London". Teddington HC.

- ^ Egan, Travie; Connolly, Helen (2005). Field hockey: rules, tips, strategy, and safety. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-0182-8.

- ^ "Teddington Athletic F.C." Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Hearts of Teddlothian F.C." Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Teddington RFC". Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Teddington Lawn Tennis Club". Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Weirside Rangers AFC". Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Teddington". Crossrail 2. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Buses from Teddington Transport for London

- ^ Jessop, Miranda. "Interview: Julian Clary on his new children's book". Essential Surrey. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Teed, Paul (19 September 2012). "Teddington's Mo Farah to be granted freedom of Richmond". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "Profile: Andrew Gilligan". BBC News. 30 January 2004. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Adams, Fiona (July 2013). "Page to Stage". Richmond Magazine.

- ^ D'Souza, Christa (25 July 2003). "Not just a pouty face". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Teddington based creator of Line of Duty backs Landmark campaign". Teddington Nub News. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Royal Richmond timeline". Local history timelines. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Luffmann Atterbury". Twickenham Museum. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Boyes, Valerie (2012). Royal Minstrels to Rock and Roll; 500 years of music-making in Richmond. London: Museum of Richmond.

- ^ "Blue Plaques in Richmond upon Thames". Visit Richmond. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Teed, Paul (24 July 2011). "Chairwoman of Friends of Teddington Memorial Hospital honoured with portrait". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England (7 January 2011). "Teddington Library (1396400)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Oxford Reference: Dorothy Edwards". Oxford University Press. 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Egmont Books Website - Dorothy Edwards". 17 October 2006. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006.

- ^ "Dr Stephen Hales. Scientist, philanthropist & curate of Teddington". Twickenham Museum. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Patterson, H M (5 October 2007). "Readers' Letters: Benny Hill's statue should be in Southampton". Southern Daily Echo. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Residences of the French Royal House of Orleans" (PDF). Local History Notes. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Buchanan, Clare (22 April 2013). "Teddington plaque pledge for South African poet Eugene Marais". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Murray-Smith, S. "Selfe, Norman (1839–1911)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Smurthwaite, Nick (14 February 2012). "John Thaxter". The Stage. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Teddington: Manor House, The Grove and other houses demolished in the 19th and 20th c". Twickenham Museum. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b Highfill, Philip H.; Burnim, Kalman A.; Langhans, Edward A. (1993). A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800. Vol. 16. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-1803-2.

Further reading

edit- Sheaf, John; Howe, Ken. Hampton and Teddington Past, Historical Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-948667-25-7

- Howe, Ken; Cherry, Mike. Twickenham, Teddington and Hampton in Old Photographs: A Second Selection (Britain in Old Photographs), Sutton Publishing, 1998. ISBN 978-0750916950

External links

edit- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911.

- British History Online – Teddington

- The Teddington Society