Syriana is a 2005 American political thriller film written and directed by Stephen Gaghan, loosely based on Robert Baer's 2003 memoir See No Evil. The film stars an ensemble cast consisting of George Clooney, Matt Damon, Jeffrey Wright, Chris Cooper, William Hurt, Tim Blake Nelson, Amanda Peet, Christopher Plummer, Alexander Siddig, and Mazhar Munir.

| Syriana | |

|---|---|

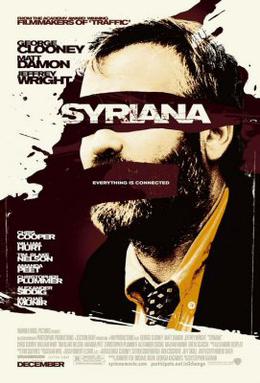

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stephen Gaghan |

| Screenplay by | Stephen Gaghan |

| Based on | See No Evil by Robert Baer |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Elswit |

| Edited by | Tim Squyres |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 128 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Arabic Urdu Persian Chinese French |

| Budget | $50 million[3] |

| Box office | $94 million[3] |

Syriana was shot in 200 locations on five continents, with large parts shot in the Middle East, Washington, D.C., and Africa.[4] In an interview with Charlie Rose, Gaghan described incidents (including planned regime changes in Venezuela) from personal meetings and interviews with the most powerful oil owners, owners of media houses, lobbyists, lawyers, and politicians which were included in the film.[5] As with Gaghan's screenplay for Traffic, Syriana uses multiple, parallel storylines, jumping among locations in Iran, Texas, Washington, D.C., Switzerland, Spain, and Lebanon.

The film received positive reviews from critics, and Clooney's performance was critically acclaimed, earning him an Academy Award and a Golden Globe Award, as well as British Academy Film Award, Critics' Choice Movie Award, and Screen Actors Guild Award nominations. Gaghan was nominated for an Academy Award and a Writers Guild of America Award for his screenplay. As of April 20, 2006, the film had grossed a total of $50.82 million at the U.S. box office and $43.2 million overseas, for a total of $94 million.

Gaghan changed the names of entities currently operating in the Middle East, while retaining their place in the story. Committee for the Liberation of Iran was based on an organization called Committee for the Liberation of Iraq.[6]

Plot

editU.S. energy giant Connex Oil is losing control of key oil fields in a Persian Gulf kingdom ruled by the Al-Subaai family. The Emirate's foreign minister, Prince Nasir, has granted natural gas drilling rights to a Chinese company, greatly upsetting the U.S. oil industry and the U.S. government. To compensate for its decreased production capacity, Connex initiates a shady merger with Killen, a smaller oil company that recently won the drilling rights to Kazakhstan's Tengiz Field. If Connex-Killen were a country, it would rank as the world's twenty-third largest economy, and antitrust regulators at the Department of Justice (DOJ) have concerns. Whiting-Sloan, a Washington, D.C.-based law firm headed by Dean Whiting is hired to smooth the way for the merger. Bennett Holiday, an associate of that firm, is assigned to promote the impression of due diligence to the DOJ, deflecting any allegations of corruption.

Emir storyline

editBryan Woodman is an American energy analyst based in Geneva. Woodman's supervisor directs him to attend a private party hosted by the Emir at his private estate in Marbella, Spain, to offer his company's services. The Emir's illness during the party prevents Woodman from speaking directly with him while, at the same time, the Emir's younger son, Prince Meshal Al-Subaai, shows the estate's many rooms and areas to Chinese oil executives via remote-controlled cameras. No one notices that a crack in one of the swimming pool area's underwater lights has electrified the water. Just as Woodman and all the other guests are brought to the pool area, Woodman's son jumps into the pool and is electrocuted.

In reparation and out of sympathy for the loss of his son, Prince Nasir, the Emir's older son, grants Woodman's company oil interests worth $75 million. Woodman, though initially insulted by the offer, gradually becomes his economic advisor. Prince Nasir is dedicated to the idea of progressive reform and understands that oil dependency is not sustainable in the long term; Nasir wants to utilize his nation's oil profits to diversify the economy and introduce democratic reforms, in sharp contrast to his father's repressive government, which has been supported by American interests. His father, at the urging of the American government with the help of Whiting and his law firm, names the younger Meshal as his successor, causing Nasir to attempt a coup.

Assassination storyline

editBob Barnes is a veteran CIA officer trying to stop illegal arms trafficking in the Middle East. His dedication went up to the point of speaking Farsi fluently. While on assignment in Tehran to kill two arms dealers, Barnes notices that one of two anti-aircraft missiles intended to be used in a bombing was diverted to an Egyptian, while the other explodes and kills the two arms dealers. The dealers are later revealed to be Iranian Intelligence agents. Barnes makes his superiors nervous by writing memos about the missile theft and is subsequently reassigned to a desk job. However, unaccustomed to the political discretion required, he quickly embarrasses the wrong people by speaking his mind and is sent back to the field with the assignment of assassinating Prince Nasir, whom the CIA misidentifies as being the financier behind the Egyptian's acquisition of the missile. Prior to his reassignment, Barnes confides in his ex-CIA officer friend, Stan Goff, that he will return to Lebanon. Goff advises him to clear his presence with Hezbollah so they know he is not acting against them. Barnes travels to Lebanon, obtains safe passage from a Hezbollah leader, and hires a mercenary named Mussawi to help kidnap and kill Nasir. But Mussawi has become an Iranian agent and has Barnes abducted. Mussawi tortures Barnes and prepares to behead him, but the Hezbollah leader arrives and stops him.

When the CIA learns that Mussawi plans to broadcast the agency's intention to kill Nasir, they set Barnes up as a scapegoat, portraying him as a rogue officer. Barnes's boss, Terry George, worries that Barnes might talk about the Nasir assassination plan and that killing Nasir with a drone would make it obvious as an American-backed assassination. He has Barnes's passports revoked, locks him out of his computer at work, and initiates an investigation of him. Barnes, however, learns from Goff that Whiting, working on behalf of a group of businessmen calling themselves "The Committee to Liberate Iran", is responsible for Barnes's blackballing and the assassination, and threatens Whiting and his family unless he halts the investigation and releases Barnes's passports.

Barnes returns to the Middle East and approaches Prince Nasir's convoy to warn him of the assassination plan. As he arrives, a guided bomb from a circling Predator drone strikes the automobile of Nasir and his family, killing them and Barnes instantly. Woodman, having earlier offered his seat in Nasir's car to a member of the prince's family, survives the drone strike and goes home to his wife and remaining son.

Wasim storyline

editPakistani migrant workers Saleem Ahmed Khan and his son Wasim board a bus to go to work at a Connex refinery, only to discover that they have been laid off. Since the company had provided food and lodging, the workers face the threat of deportation due to their unemployed status. Wasim desperately searches for work but is refused because he doesn't speak Arabic well. Wasim and his friend join a madrasa to learn Arabic in order to improve their employment prospects. While playing soccer, they meet a charismatic Islamic fundamentalist, the same man who received the missing Iranian missile, who eventually leads them to use it while executing a suicide attack on a Connex-Killen tanker.

Merger storyline

editBennett Holiday meets with Dean Whiting, who is convinced that Killen bribed someone to get the drilling rights in Kazakhstan. While investigating Connex-Killen's records, Holiday discovers a wire transfer of funds that leads back to a transaction between Texas oilman and Killen colleague Danny Dalton and Kazakh officials. Holiday tells Connex-Killen of his discovery, and they pretend not to have known about it. Holiday advises Dalton that he will likely be charged with corruption in order to serve as a "body" to get the DOJ off the back of the rest of Connex-Killen. U.S. Attorney Donald Farish III then strong-arms Holiday into giving the DOJ information about illegal activities he has discovered. Holiday gives up Dalton, but Farish says this is not enough. Holiday meets with the CEO of Killen Oil, Jimmy Pope, and informs him that the DOJ needs a second body in order to drop the investigation and allow the merger. Pope asks Holiday whether a person at Holiday's firm above him would be sufficient as the additional body. Holiday says yes, as long as the name were big enough.

Holiday is brought by his colleague and mentor Sydney Hewitt to meet with the Chairman & CEO of Connex Oil, Leland "Lee" Janus. Holiday reveals an under-the-table deal that Hewitt made while the Connex-Killen merger was being processed. Holiday has given Hewitt to the DOJ as the second body, thereby protecting the rest of Connex-Killen. Janus is able to accept the "Oil Industry Man of the Year" award with a load taken off his shoulders.

Cast

edit- Kayvan Novak as Arash

- George Clooney as Bob Barnes

- Amr Waked as Mohammed Sheik Agiza

- Christopher Plummer as Dean Whiting

- Jeffrey Wright as Bennett Holiday

- Chris Cooper as Jimmy Pope

- Robert Foxworth as Tommy Barton

- Nicky Henson as Sydney Hewitt

- Nicholas Art as Riley Woodman

- Matt Damon as Bryan Woodman

- Amanda Peet as Julie Woodman

- Steven Hinkle as Max Woodman

- Daisy Tormé as Rebecca

- Peter Gerety as Leland Janus

- Richard Lintern as Bryan's Boss

- Jocelyn Quivrin as Vincent

- Mazhar Munir as Wasim Khan

- Shahid Ahmed as Saleem Ahmed Khan

- Roger Yuan as Chinese Engineer

- Jayne Atkinson as Division Chief

- Tom McCarthy as Fred Franks

- Jamey Sheridan as Terry

- Max Minghella as Robby Barnes

- Nadim Sawalha as Emir Hamed Al-Subaai

- Alexander Siddig as Prince Nasir Al-Subaai

- William Charles Mitchell as Bennett Holiday Sr.

- Tim Blake Nelson as Danny Dalton

- David Clennon as Donald

- William Hurt as Stan

- Mark Strong as Mussawi/Jimmy

- Will McCormack as Willy

- Michael Allinson as Sir David

Production

editWhile working on Traffic, Stephen Gaghan began to see parallels between drug addiction and America's dependency on foreign oil.[7] Another source of inspiration came from 9/11 and Gaghan's lack of knowledge about the Middle East. He said, "When 9/11 happened, it suddenly was a war on terror, which I think of as a war on emotions. It all started to click for me."[8] A few weeks after 9/11, Steven Soderbergh sent Gaghan a copy of ex-CIA officer Robert Baer's memoir, See No Evil.[9] The screenwriter read the book and wanted to turn it into a film because it added another layer to the story that Gaghan wanted to tell.[7] Soderbergh bought the rights to See No Evil and negotiated the deal with Warner Bros.[10]

Gaghan met Baer for lunch and then, for six weeks in 2002, the two men traveled from Washington to Geneva to the French Riviera to Lebanon, Syria and Dubai, meeting with lobbyists, arms dealers, oil traders, Arab officials and the spiritual leader of Hezbollah.[9] Meeting Baer, Gaghan realized that the man had "gone out there and done and seen things that he was not allowed to talk about, and wouldn't, but he was angry about and also trying to make amends for."[9] Before any filming took place, Gaghan convinced Warner Bros. to give him an unlimited research budget and no deadline.[10] He did his own legwork, meeting with oil traders in London and lawyers in Washington, D.C. Moments after arriving in Beirut in 2002, Gaghan was taken from the airport in a blindfold and hood where he met with Sheik Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah, who was interested in films. He decided to grant the writer an audience even though he had not requested one. In addition, Gaghan dined with men suspected of killing former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri and met with former Defense Policy Board chairman Richard Perle.[10]

Gaghan has cited as influences on Syriana, European films like Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City, Costa Gavras' Z, and Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers.[11]

Another influence, or resource—one that might also explain the movie's use of a documentary clip featuring John D. Rockefeller—is the fact that Gaghan's fashion-designer wife Minnie Mortimer is the great-granddaughter of onetime Standard Oil executive Henry Morgan Tilford.

Harrison Ford turned down the role of Bob Barnes (the role played by George Clooney), regretting it later, stating, "I didn't feel strongly enough about the truth of the material and I think I made a mistake."[12] This is the second Stephen Gaghan-written role Ford has declined, having turned down the role of Robert Wakefield in Traffic, a role that eventually went to Michael Douglas.[13]

Principal photography

editGaghan shot in over 200 locations on four continents with 100 speaking parts.[11] Syriana originally had five storylines, all of which were filmed. The fifth storyline, centering on Michelle Monaghan playing a Miss USA who becomes involved with a rich Arab oilman, was cut when the film became too complicated.[7][11] Also, a role played by Greta Scacchi, as Bob Barnes' wife, was also cut before the final release. Parts of the film were shot in Lebanon, Dubai and other parts of the Middle East.[14]

During filming, Clooney suffered an accident on the set which caused a brain injury with complications from a punctured dura.[15]

Score

editTitle

editThe film's title is suggested to derive from the hypothesized Pax Syriana, as an allusion to the necessary state of peace between Syria and the U.S. as it relates to the oil business. In a December 2005 interview, Baer told NPR that the title is a metaphor for foreign intervention in the Middle East, referring to post-World War I think tank strategic studies for the creation of an artificial state (such as Iraq, created from elements of the former Ottoman Empire) that ensured continued western access to crude oil.[16]

The movie's website states that "‘Syriana’ is a real term used by Washington think-tanks to describe a hypothetical reshaping of the Middle East."[17] Gaghan said he saw Syriana as "a great word that could stand for man's perpetual hope of remaking any geographic region to suit his own needs."[18] The word Syriana derives from Syria + the Latin suffix -ana; it means, roughly, "in the manner of Syria." Historically, Syria refers not to the state that since 1944 has borne the name, but to a more extensive land stretching from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea to the middle Euphrates River and the western edge of the desert steppe, and from the Tauric system of mountains in the north to the edge of the Sinai desert in the south. This land was part of the Fertile Crescent, and has historically been a geopolitically crucial junction for trade routes from the east, from Asia Minor and the Aegean, and from Egypt, and has long been a focus of great power conflicts. The word Syria does not appear in the Hebrew original of the Scriptures, but appears in the Septuagint as the translation of Aram. Herodotus speaks of "Syrians" as identical with Assyrians, but the term's geographical significance was not well defined in pre-Greek and Greek times. As an ethnic term, "Syrian" came to refer in Antiquity to Semitic peoples living outside Mesopotamian and Arabian areas. Greco-Roman administrations were the first to apply the term to a definite district.[19]

Release

editSyriana was released on November 23, 2005 in limited release in only five theaters grossing $374,502 on its opening weekend. It went into wide release on December 9, 2005 in 1,752 theaters grossing $11.7 million on that weekend. It went on to make $50.8 million in North America and $43.2 million in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $94 million.[20] Censor authorities in some parts of the Middle East censored parts of the movie, because it depicted foreigners being ill-treated. Although abuse of foreign workers is rife, the censor authorities deemed such scenes as insulting.[21]

Reception

editCritical reception

editSyriana received generally positive reviews, mostly for Clooney's performance and Gaghan's screenplay. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, it has a rating of 73% based on 198 reviews, with an average score of 6.89/10. The website's consensus states, "Ambitious, complicated, intellectual, and demanding of its audience, Syriana is both a gripping geopolitical thriller and wake-up call to the complacent."[22] The film has a score of 76 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 40 critics indicating "generally favorable reviews".[23] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C" on an A+ to F scale.

As a motion picture, the main criticism, even among reviewers who praised the film, was the confusion created by following numerous stories. Most critics stated that it was almost impossible to follow the plot, though some, notably Roger Ebert, praised precisely that quality of the film and offered an interesting hidden story possibility (a covert deal between the U.S. and China involving oil being shipped through Kazakhstan and passed off as coming from a different source).[24] The audience confusion mimics the confusion of the characters, who are enmeshed in the events around them without a clear understanding of what precisely is going on. As with Gaghan's screenplay for Traffic, Syriana uses multiple, parallel storylines, jumping from locations in Texas, Washington D.C., Switzerland, Spain, and the Middle East, leading film critic Ebert to describe the film as hyperlink cinema.[24]

Time magazine's Richard Corliss wrote, "Gaghan relies on Clooney's agnostic heroism to lure viewers into his maze. When they get there, they will find not a conventionally satisfying movie but a kind of illustrated journalism: an engrossing, insider's tour of the world's hottest spots, grandest schemes and most dangerous men."[25] In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan wrote, "This is conspiracy-theory filmmaking of the most bravura kind, but if only a fraction of its suppositions are true, we—and the world—are in a world of trouble."[26] USA Today gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote, "Gaghan assumes his audience is smart enough to follow his explosive tour of global petro-politics. The result is thought-provoking and unnerving, emotionally engaging and intellectually stimulating."[27] Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B−" rating and Lisa Schwarzbaum wrote, "it's also the kind of movie that requires a viewer to work actively for comprehension, and to chalk up any lack of same to his or her own deficiency in the face of something so evidently smart."[28]

In his review for The New York Observer, Andrew Sarris wrote: "If anything, Syriana tends to oversimplify a mind-bogglingly multifaceted problem that cannot so easily be resolved by a diatribe against the supposedly all-powerful 'Americans.'"[29] Rolling Stone magazine's Peter Travers gave the film his highest rating and praised George Clooney's performance: "This is the best acting Clooney has ever done—he's hypnotic, haunting and quietly devastating."[30] Philip French, in his review for The Observer, praised the film as "thoughtful, exciting and urgent".[31] In his review for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw wrote, "But what complicates the plot is writer-director Stephen Gaghan's reluctance to criticise America too much. Instead of complexity, there is a blank, uncompelling tangle, which conceals a kind of complacent political correctness."[32]

Ebert named it the second-best film of 2005, behind Crash. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone named it as the third best film of 2005.[33] Entertainment Weekly ranked Syriana as one of the 25 "Powerful Political Thrillers" in film history.[34]

Top ten lists

editSyriana was listed on many critics' top ten lists.[35]

- 1st – Richard Roeper, Ebert & Roeper[36]

- 2nd – Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

- 2nd – James Berardinelli, Reelviews

- 2nd – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times

- 3rd – Christy Lemire, Associated Press[37]

- 3rd – Alison Benedikt, Chicago Tribune

- 3rd – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 4th – Ann Hornaday, Washington Post

- 6th – David Germain, Associated Press[37]

- 7th – Rene Rodriguez, Miami Herald

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Carrie Rickey, Philadelphia Inquirer

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Carina Chocano, Los Angeles Times

Accolades

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ Although an adaptation of See No Evil, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences nominated it in the Best Original Screenplay category rather than Best Adapted Screenplay, citing the film's numerous differences from the source material as enough to classify it as original.[41]

References

edit- ^ "Everything Is Connected". CBS News. 22 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ "Syriana (15)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ a b "Syriana (2005)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ "Stephen Gaghan interview on Syriana". KXM / You tube channel.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Rose, Charlier (9 December 2005). "Interview with Stephen Gaghan". Charlie Rose. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Slevin, Peter. "New Group Aims to Drum Up Backing for Ousting Hussein". Archived from the original on 2002-11-05.

- ^ a b c Grady, Pam (December 16, 2005). "Syriana, Staccato Style". FilmStew. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ Nguyen, Ky N (January 2006). "Tracks of Terrorism". The Washington Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ a b c Halbfinger, David M (May 15, 2005). "Hollywood has a Hot New Agency". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ a b c Tyrangiel, Josh (November 13, 2005). "So, You Ever Kill Anybody?". Time. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ a b c Farber, Stephen (November 13, 2005). "A Half-Dozen Ways to Watch the Same Movie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ Harrison Ford: 'I should have been in Syriana' Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daly, Steve (2001-03-02). "Dope & Glory". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ Vinita Bharadwaj, Staff Reporter (4 December 2004). "How Hollywood located Dubai". GulfNews. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "George Clooney – Clooney Contemplated Suicide Over Brain Injury". Contact Music. October 23, 2005. Archived from the original on January 20, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

- ^ "Ex-CIA Agent Robert Baer, Inspiration for 'Syriana'". NPR. 6 December 2005. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Syriana Blu-ray". www.WBShop.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2005-12-23.

- ^ Stephen Gaghan's discussion Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine with The Washington Post in November 2005

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed.

- ^ "Syriana". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Jerome Taylor (20 April 2006). "Dubai censor cuts scenes of labour abuse from 'Syriana'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-26.

- ^ "Syriana". Rotten Tomatoes. 9 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Syriana". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2019-10-13. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (December 8, 2005). "Syriana". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (November 21, 2005). "A Thriller That Thinks". Time. Archived from the original on November 25, 2005. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (November 23, 2005). "Syriana". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (November 22, 2005). "Syriana explodes on the screen". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2008-11-03. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (November 22, 2005). "Syriana". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2009-04-21. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (December 4, 2005). "Soderbergh, Clooney and Co. Make Mideast Mess Too Simple". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 2014-07-26. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ^ Travers, Peter (November 17, 2005). "Syriana". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 21, 2006. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ French, Philip (March 5, 2006). "Syriana". The Observer. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (March 3, 2006). "Syriana". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 16, 2005). "King Clooney and the 10 Best Movies of 2005". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ "Democracy 'n' Action: 25 Powerful Political Thrillers". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2009-09-04. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ^ "Metacritic: 2005 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. December 14, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Ebert and Roeper Top Ten Lists (2000-2005))". www.innermind.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Flick picks of 2005". nwitimes.com. Associated Press. January 2006. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ^ "The 78th Academy Awards (2006) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Tim (January 31, 2006). "Academy Award Noms: Oscar's western union". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (March 5, 2006). "Party crashed . . . big time". Variety. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Karger, Dave (January 27, 2006). "Syriana undergoes a script change". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Feinberg, Lexi (December 29, 2005). "Crash Speeds To The Top". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "African American Film Critics Association Select Crash as The Top Film of 2005". BlackFilm. December 21, 2005. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "AAFCA 2005 Film Selections". African-American Film Critic’s Association. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2005: AFI Movies of the Year". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ King, Susan (December 12, 2005). "Brokeback picks up honors, nominations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "10th ADG Awards: Winners & Nominees". Art Directors Guild. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ McNary, Dave (January 17, 2006). "Pic palette for art directors' kudos". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "2006 Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "2005 Awards". Austin Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "Syriana remporte le prix de l'UCC". La Libre Belgique (in French). January 7, 2007. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Boston film crix hail Brokeback, Capote". Variety. December 11, 2005. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "British Academy Film Awards 2006". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (February 19, 2006). "Brits back Brokeback". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Vary, Adam (February 12, 2006). "BAFTAs dig beyond national treasures". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "Costume Guild reveals noms". Variety. January 11, 2006. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "The 11th Critics' Choice Movie Awards Winners and Nominees". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Seif, Dena (December 11, 2005). "B'cast crix back Brokeback". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Tyler, Joshua (December 19, 2005). "DFWFCA Awards Ang". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Jorgenson, Todd (December 20, 2005). "Dallas–Fort Worth Film Critics 2005 Awards". RottenTomatoes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "2006 Edgar Nominees & Winners". Mystery Writers of America. Archived from the original on May 13, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ "16th Annual Environmental Media Awards". Environmental Media Association. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Media Goes Green". CBS News. November 9, 2006. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 2006". Golden Globes. Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA). Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "Live coverage of 2006 Golden Globes". Variety. January 16, 2006. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Winners of the 7th Annual Golden Trailer Awards". Golden Trailer Awards. Archived from the original on July 5, 2006. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "2005 Honorees". Hollywood Film Awards. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "Hollywood Film Festival Bestows Kudos, Stephen Frears's Mrs. Henderson Presents & George Lucas's Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith Among Winners". Hollywood Film Festival. October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on December 11, 2005. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "George Lucas' Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith wins Hollywood Movie of the Year Award". Hollywood Film Festival. October 18, 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Schneider, Michael (January 10, 2006). "Crash tops NAACP noms". Variety. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "37th Annual Image Awards nominations". Variety. February 23, 2006. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Awards for 2005". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Mohr, Ian (December 12, 2005). "NBR in 'Good' mood". Variety. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Fauth, Jurgen; Dermansky, Marcy. "The New York Film Critics Online Awards 2005". Worldfilm Guide. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ Douglas, Edward (December 11, 2005). "2005 NYFCO Film Awards". New York Film Critics Online. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ "Robert Nomineringer for året: 2007". Danish Film Academy (in Danish). Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "Film-kamp i Robertnomineringerne". DR (in Danish). December 13, 2006. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "Screen Actors Guild Honors Outstanding Film and Television Performances in 13 Categories at the 12th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "SAG Awards 2006: Full list of winners". BBC News. January 30, 2006. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Nominations Announced for the 12th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Awards". St. Louis Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "2005 Stinkers Awards Announced". Rotten Tomatoes. March 3, 2006. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "The Worst of 2005". Stinkers Bad Movie Awards. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "SİYAD'ın seçtikleri..." Türkiye (in Turkish). June 16, 2006. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Sinema yazarları Saklıyı buldu". Sabah (in Turkish). June 4, 2006. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "SİYAD Ödülleri̇ İçi̇n Adaylar Açiklandi". Medyatava (in Turkish). 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Çilingir, Sadi (January 15, 2007). "SİYAD Ödülleri 39. Kez Sahiplerini Buldu". Sadibey (in Turkish). Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "18th Annual USC Scripter Award Winner Announced". University of Southern California. January 18, 2006. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (January 4, 2006). "WGA Announces Nominees for Writers Guild Awards". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

External links

edit- Official website

- Syriana screenplay

- Syriana at IMDb

- Syriana at AllMovie

- Syriana at Rotten Tomatoes

- Syriana at Metacritic

- Syriana at Box Office Mojo

- The Tangled Web of Syriana - Image - Diagram explaining, in detail, the plot of Syriana.

- Map of Forces, Acts and Geography