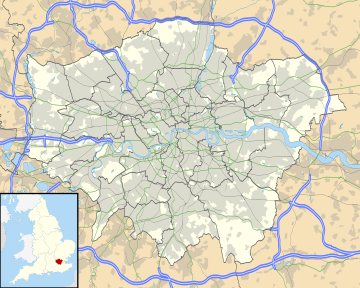

Camberwell (/ˈkæmbərwɛl/ KAM-bər-wel) is an area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark, 2+3⁄4 miles (4.5 kilometres) southeast of Charing Cross.

Camberwell was first a village associated with the church of St Giles and a common of which Goose Green is a remnant. This early parish included the neighbouring hamlets of Peckham, Dulwich, Nunhead, and part of Herne Hill (the rest of Herne Hill was in the parish of Lambeth).[1] Until 1889, it was part of the county of Surrey. In 1900 the original parish became the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell.

In 1965, most of the Borough of Camberwell was merged into the London Borough of Southwark.[2] To the west, part of both West Dulwich and Herne Hill come under the London Borough of Lambeth.

The place now known as Camberwell covers a much smaller area than the ancient parish, and it is bound on the north by Walworth; on the south by East Dulwich and Herne Hill; to the west by Kennington; and on the east by Peckham.[3]

History

editCamberwell appears in the Domesday Book as Cambrewelle.[4] The name may derive from the Old English Cumberwell or Comberwell, meaning 'Well of the Britons', referring to remaining Celtic inhabitants of an area dominated by Anglo-Saxons.[5] An alternative theory suggests the name may mean 'Cripple Well', and that the settlement developed as a hamlet where people from the City of London were expelled when they had a contagious disease like leprosy, for treatment by the church and the clean, healing waters from the wells.[citation needed] Springs and wells are known to have existed on the southern slope of Denmark Hill, especially around Grove Park.

It was already a substantial settlement with a church when mentioned in the Domesday Book, and was the parish church for a large area including Dulwich and Peckham. It was held by Haimo the Sheriff (of Kent). Its Domesday assets were: 6 hides and 1 virgate (i.e. 750 acres or 300 hectares); 1 church, 8 ploughs, 63 acres (25 hectares) of meadow, woodland worth 60 hogs. It rendered £14. Up to the mid-19th century, Camberwell was visited by Londoners for its rural tranquillity and the reputed healing properties of its mineral springs. Like much of inner South London, Camberwell was transformed by the arrival of the railways in the 1860s.[5] Camberwell Green is now a very small area of common land; it was once a traditional village green on which was held an annual fair, of ancient origin, which rivalled that of Greenwich.[6]

There is evidence of a black community residing in Camberwell, made up mostly of enslaved people from Africa and North America during the 18th and 19th centuries.[7] Some of these people fled their slavery in an attempt to create a new life for themselves in the streets of London. While very little is known about most of the escapees, some insight can be gained into the life of sailor James Williams, an enslaved man from the Caribbean.[8][9]

Local government

editThe parish of Camberwell

editCamberwell St Giles is the name given to an ancient, and later civil, parish in the Brixton hundred of Surrey.[10][11] The parish covered 4,570 acres (1,850 hectares) in 1831 and was divided into the liberty of Peckham to the east and the hamlet of Dulwich to the southwest, as well as Camberwell proper. The parish tapered in the south to form a point in what is now known as the Crystal Palace area.[11] In 1801, the population was 7,059 and by 1851 this had risen to 54,667.[12] In 1829, it was included in the Metropolitan Police District and in 1855 it was included in the area of responsibility of the Metropolitan Board of Works, with Camberwell Vestry nominating one member to the board. In 1889 the board was replaced by the London County Council and Camberwell was removed administratively from Surrey to form part of the County of London.[13]

The Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell

editIn 1900, the area of the Camberwell parish became the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell.[14] In 1965, the metropolitan borough was abolished and its former area became the southern part of the London Borough of Southwark in Greater London. The western part of the area is situated in the adjacent London Borough of Lambeth.

Industrial history

editThe area has historically been home to many factories, including R. White's Lemonade, which originated in Camberwell, as well as Dualit toasters.[15] Neither of these companies is now based in the area.

Former schools

editWilson's School was founded in 1615 in Camberwell by royal charter by Edward Wilson, vicar of the Parish of Camberwell. The charter was granted by James I. The school moved to its current site in Croydon in 1975. A school for girls, Mary Datchelor Girls' School, was established in Camberwell in 1877. It was built on two houses at 15 and 17 Grove Lane, the location of a former manor house. All except one of its 30 pupils came from the parish of St Andrew Undershaft in the City of London. The funding for the school came from a bequest from Mary Datchelor, who died childless. Proceeds of a property in Threadneedle Street used as a coffee-house were used to pay for apprenticeships for the poor boys of the parish, but as demographics in the City changed, it was decided to set up a school. By the 1970s, the school was receiving funding from the Clothworkers' Company and the Inner London Education Authority funded teaching posts. The school came under pressure from ILEA to become co-educational and comprehensive. Faced with this choice or becoming fully private, the school's governors instead decided to close in 1981. The school buildings were later used as offices for the charity Save the Children but have now been converted to flats.[16][17][18] Camberwell Collegiate School was an independent school located on the eastern side of Camberwell Grove, directly opposite the Grove Chapel. The Collegiate College had some success for a while, and led to the closure for some decades of the Denmark Hill Grammar School. However it had difficulty competing with other nearby schools including Dulwich College, and was closed in 1867.The land was sold for building.[19] [20] [21]

Important buildings

editCamberwell today is a mixture of relatively well preserved Georgian and 20th-century housing, including a number of tower blocks. Camberwell Grove, Grove Lane and Addington Square have some of London's most elegant and well-preserved Georgian houses.

The Salvation Army's William Booth Memorial Training College, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, was completed in 1932: it towers over South London from Denmark Hill. It has a similar monumental impressiveness to Gilbert Scott's other local buildings, Battersea Power Station and the Tate Modern, although its simplicity is partly the result of repeated budget cuts during its construction: much more detail, including carved Gothic stonework surrounding the windows, was originally planned. Camberwell is home to one of London's largest teaching hospitals, King's College Hospital with associated medical school the Guy's King's and St Thomas' (GKT) School of Medicine. The Maudsley Hospital, an internationally significant psychiatric hospital, is located in Camberwell along with the Institute of Psychiatry.[22]

Early music halls in Camberwell were in the back hall of public houses. One, the "Father Redcap" (1853) still stands by Camberwell Green, but internally, much altered. In 1896, the Dan Leno company opened the "Oriental Palace of Varieties", on Denmark Hill. This successful venture was soon replaced with a new theatre, designed by Ernest A.E. Woodrow and with a capacity of 1,553, in 1899, named the "Camberwell Palace". This was further expanded by architect Lewen Sharp in 1908.[23] By 1912, the theatre was showing films as a part of the variety programme and became an ABC cinema in September 1932 – known simply as "The Palace Cinema". It reopened as a variety theatre in 1943, but closed on 28 April 1956 and was demolished.[24]

Nearby, marked by Orpheus Street, was the "Metropole Theatre and Opera House", presenting transfers of West End shows. This was demolished to build an Odeon cinema in 1939. The cinema seated 2,470, and has since been demolished.[25] A second ABC cinema, known originally as the Regal Cinema and later as the ABC Camberwell, opened in 1940. With only one screen but 2,470 seats, the cinema was one of the largest suburban cinemas in London and continued to operate until 1973, after which it was used as a bingo hall until February 2010. The building retains its Art Deco style and is Grade II listed.[26]

The Church of the Sacred Heart, Camberwell has been listed Grade II on the National Heritage List for England since 2015.[27] Camberwell Town Hall, designed by Culpin and Bowers, was completed in 1934.[28]

On 3 July 2009 a major fire swept through Lakanal House, a twelve-storey tower block. Six people were killed and at least 20 people were injured.

Camberwell beauty

editThe Camberwell beauty (also Camberwell Beauty) is a butterfly (Nymphalis antiopa) which is rarely found in the UK – it is so named because two examples were first identified on Coldharbour Lane, Camberwell in 1748.[29] A large mosaic of the Camberwell beauty used to adorn the Samuel Jones paper factory on Southampton Way. The paper factory has since been demolished but the mosaic was removed and re-installed on the side of Lynn Boxing Club on Wells Way.

Culture

editArt

editCamberwell has several art galleries including Camberwell College of Arts, the South London Gallery and numerous smaller commercial art spaces. There is an annual Camberwell Arts Festival in the summer.[30] The Blue Elephant Theatre on Bethwin Road is the only theatre venue in Camberwell.[31]

A group now known as the YBAs (the Young British Artists) began in Camberwell – in the Millard building of Goldsmiths' College on Cormont Road. A former training college for women teachers, the Millard was the home of Goldsmiths Fine Art and Textiles department until 1988. It was converted to flats in 1996 and is now known as St Gabriel's Manor.

The core of the later-to-be YBAs, graduated from the Goldsmiths BA Fine Art degree course in the classes of 1987–90. Liam Gillick, Fiona Rae, Steve Park and Sarah Lucas, were graduates in the class of 1987. Ian Davenport, Michael Landy, Gary Hume, Anya Gallaccio, Henry Bond and Angela Bulloch, were graduates in the class of 1988; Damien Hirst, Angus Fairhurst, Mat Collishaw, Simon Patterson, and Abigail Lane, were graduates from the class of 1989; whilst Gillian Wearing, and Sam Taylor-Wood, were graduates from the class of 1990. During the years 1987–90, the teaching staff on the Goldsmiths BA Fine Art included Jon Thompson, Richard Wentworth, Michael Craig-Martin, Ian Jeffrey, Helen Chadwick, Mark Wallinger, Judith Cowan and Glen Baxter. Collishaw has a studio in a pub in Camberwell.[32] as does the sculptor Anish Kapoor.[33]

In his memoir Lucky Kunst, artist Gregor Muir, writes:

- Not yet housed in the university building at New Cross to which it eventually moved in the late 1980s, Goldsmiths was a stone's throw away in Myatts Field on the other side of Camberwell Green. In contrast to Camberwell's Friday night bacchanal, Goldsmith's held its disco on a Tuesday evening with dinner ladies serving drinks, including tea, from a service hatch. This indicated to me that Goldsmiths was deeply uncool.

The building was also the hospital where Vera Brittain served as a nurse and described in her memoir Testament of Youth.[34]

Literature

editThomas Hood, humorist and author of "The Song of the Shirt", lived in Camberwell from 1840 for two years; initially at 8, South Place, (now 181, Camberwell New Road). He later moved to 2, Union Row (now 266, High Street). He wrote to friends praising the clean air. In late 1841, he moved to St John's Wood.[35] The Victorian art critic and watercolourist John Ruskin lived at 163 Denmark Hill from 1847, but moved out in 1872 as the railways spoiled his view.[36] Ruskin designed part of a stained-glass window in St Giles' Church, Camberwell.[37] Ruskin Park is named after him, and there is also a John Ruskin Street.

Another famous writer who lived in the area was the poet Robert Browning, who was born in nearby Walworth, and lived there until he was 28.[38] Novelist George Gissing, in the summer of 1893, took lodgings at 76 Burton Road, Brixton. From Burton Road he went for long walks through nearby Camberwell, soaking up impressions of the way of life he saw emerging there."[39] This led him to writing In the Year of Jubilee, the story of "the romantic and sexual initiation of a suburban heroine, Nancy Lord." Gissing originally called his novel Miss Lord of Camberwell.[40]

Muriel Spark, the author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and The Ballad of Peckham Rye lived, between 1955 and 1965, in a bedsit at 13 Baldwin Crescent, Camberwell.[41] The novelist Mary Jane Staples, who grew up in Walworth, wrote a book called The King of Camberwell, the third instalment of her Adams family saga about Cockney life. Comedian Jenny Eclair is a long-term resident of Camberwell, and the area features in her 2001 novel Camberwell Beauty, named after a species of butterfly. Playwright Martin McDonagh and his brother, writer/director John Michael McDonagh, live in Camberwell. The 2014 novel The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters is set in 1920s Camberwell.[42] In Daniel Defoe's novel Roxana (1724) the eponymous protagonist imagines her daughter, Susan, "drown'd in the Great Pond at Camberwell".

Nearby Peckham Rye was an important in the imaginative and creative development of poet William Blake, who, when he was eight, claimed to have seen the Prophet Ezekiel there under a bush, and he was probably ten years old when he had a vision of angels in a tree.[43]

Film

editCamberwell is referred to in the film Withnail and I – "Camberwell carrot" is the name of the enormous spliff rolled using 12 rolling papers, by Danny the dealer. His explanation for the name is, "I invented it in Camberwell and it looks like a carrot".[citation needed]

Music

editThe avant-garde band Camberwell Now named themselves after the area.

Basement Jaxx recorded three songs about Camberwell: "Camberwell Skies", "Camberskank" and "I live in Camberwell"[44] which are on The Singles: Special Edition album (2005).

Florence Welch from British indie-rock band Florence and the Machine wrote and recorded a song entitled "South London Forever" on her 2018 album High as Hope based on her experience growing up in Camberwell, naming places such as the Joiners Arms and the Horniman Museum.[45]

Festivals

editCamberwell has played host to many festivals over the years, with the long-running Camberwell Arts Festival celebrating 20 years in 2014, and Camberwell Fair taking place on Camberwell Green in 2015, 2017 and 2018, resurrecting an ancient Fair that took place on the same green from 1279 to 1855.{[46] Since 2013, there is also an annual 10-day film festival – Camberwell Free Film Festival (CFFF) which is usually held in March/April in addition to special one-off screenings at other times of the year.[47]

Transport

editHistory

editUntil the First World War, Camberwell was served by three railway stations – Denmark Hill, Camberwell Gate (near Walworth), and Camberwell New Road in the west. Camberwell Gate and Camberwell New Road were closed in 1916 'temporarily' because of war shortages, but were never reopened.[48][49]

London Underground has planned a Bakerloo line extension to Camberwell on at least three occasions since the 1930s.[50]

Rail

editDenmark Hill and Loughborough Junction railway stations serve Camberwell, whilst Peckham Rye and East Dulwich are both approximately one mile (1.5 kilometres) from Camberwell Green. These stations are all in London fare zone 2.[51] London Overground, Southeastern, and Thameslink trains serve Denmark Hill. There are regular rail services to various destinations across Central London. There are also direct rail links to destinations elsewhere in London and the South East from Denmark Hill.

London Overground connects the area directly to Clapham and Battersea in the west, and Canada Water and Dalston east London. Thameslink trains carry passengers to Kentish Town in the north, whilst some peak-time services continue to destinations in Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, such as Luton Airport. Eastbound Thameslink services travel towards Orpington or Sevenoaks, via Peckham, Catford, and Bromley, amongst other destinations. Southeastern trains eastbound serve destinations in South East London and Kent, including Peckham, Lewisham, Gravesend, and Dover.[51]

Loughborough Junction is on the Thameslink route between St Albans City and Sutton. This provides Camberwell with a direct link southbound to Herne Hill, Streatham, Tooting, Wimbledon, Mitcham, and Sutton, amongst other destinations in South London. Northbound services run through the City of London and St Pancras. Destinations north of St Pancras include Kentish Town and West Hampstead. A limited Southeastern service between Blackfriars and Kent runs through Loughborough Junction.[51]

Bus

editCamberwell is served by numerous London Bus routes.

Notable residents

editResidents of the area have included children's author Enid Mary Blyton, who was born at 354 Lordship Lane, East Dulwich, on 11 August 1897 (though shortly afterwards the family moved to Beckenham),[52] and the former leader of the TGWU, Jack Jones,[53] who lived on the Ruskin House Park estate. Karl Marx initially settled with his family in Camberwell when they moved to London in 1849.[54]

Others include the former editor of The Guardian Peter Preston.[55] The Guardian columnist Zoe Williams is another resident,[56] whilst Florence Welch of the rock band Florence + the Machine also lives in the area,[57] as do actresses Lorraine Chase and Jenny Agutter.[58][59] Syd Barrett, one of the founders of Pink Floyd, studied at Camberwell College of Arts from 1964.[60]

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte gave birth to her son, Jérôme Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of the Emperor Napoleon I, in Camberwell in 1805.[61]

- Tammy Abraham, professional footballer[62]

- Henry Bessemer, inventor, had an estate in Denmark Hill[63]

- John Bostock, professional footballer[64]

- Jeremy Bowen, BBC war correspondent[65][non-primary source needed]

- Thomas Brodie-Sangster, actor and musician[66]

- Joseph Chamberlain, politician, born in Camberwell[67]

- Florence Collingbourne (1880–1946), British actress and singer[68]

- Catherine Dean, artist[69]

- Alfred Domett (1811–1887) New Zealand politician and premier from 1862–63.[70]

- Thomas Green (1659–1730)[71]

- Albert Houthuesen, artist[69]

- Marianne Jean-Baptiste, British actress, director and singer-songwriter[72]

- Ida Lupino, Hollywood film actress and director, born in Herne Hill[73]

- David McSavage, Irish stand-up[74]

- William Henry Margetson, painter

- Erin O'Connor, fashion model[75]

- Carolyn Quinn, BBC Radio 4 journalist[76]

- James Ring (1856–1939) photographer, born in Camberwell.[77]

- William Rust, British communist activist, war correspondent, and first editor of the Morning Star, born in Camberwell[78]

- Jadon Sancho, professional footballer, lived in Peckham[79]

- Edward Burnett Tylor, anthropologist[80]

- Ben Watson, professional footballer[81]

- Jack Whicher, detective[82]

- Florence Welch (b. 1986), musician and front woman of Florence and the Machine.[83]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Camberwell – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk.

- ^ Southwark London Borough Council – Community guide for Camberwell Archived 7 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Camberwell". Camberwell.

- ^ Anthony David Mills (2001). Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280106-6.

- ^ a b "Ancient well that gave name to Camberwell unearthed". The Daily Telegraph. London. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Weinreb, Ben (1986). The London Encyclopedia. Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-917561-07-8.

- ^ "Black Lives in England - Black British History in the 18th and 19th Centuries | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "4th Queen's Own Hussars | National Army Museum". www.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Runaway slave database". University of Glasgow.

- ^ "Camberwell St Giles Surrey Family History Guide". Parishmouse Surrey. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b Vision of Britain – Camberwell parish Archived 10 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine (historic map[permanent dead link])

- ^ Vision of Britain – Camberwell population

- ^ Kirby, Alison (2018). "History of Brunswick Park – Declared "one of the prettiest open spaces in south London"" (PDF). Camberwell Quarterly (196): 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Camberwell MB Archived 17 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine (historic map[permanent dead link])

- ^ "Our History - Dualit Website".

- ^ "Mary Datchelor School, Camberwell Grove – Works – Southwark Heritage". heritage.southwark.gov.uk.

- ^ Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- ^ "Mary Datchelor School – Exploring Southwark". exploringsouthwark.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Walford, Edward (1878). "Camberwell". Old and New London: Volume 6. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Aldrich, Richard (2012). "Chapter 2". School and Society in Victorian Britain: Joseph Payne and the New World of Education. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415686532.

- ^ Lewis, Samuel (1811). A topographical dictionary of England. Vol. 1 (4th ed.). London. p. 417.

- ^ "King's College London – Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience Denmark Hill Campus". King's College London. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Shaftesbury Avenue, Survey of London: volumes 31 and 32: St James Westminster, Part 2 (1963), pp. 68–84 accessed: 12 June 2008

- ^ Camberwell Palace Theatre (Cinema Treasures) accessed 12 June 2008

- ^ Camberwell Halls and Entertainment (Arthur Lloyd Theatre History) accessed: 12 June 2008

- ^ ABC Camberwell (Cinema Treasures) accessed 22 February 2010

- ^ Historic England, "Roman Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart (1422505)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 3 October 2017

- ^ Beasley, John D. (2010). Camberwell Through Time. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1848685635.

- ^ Vanessa, Fonesca. "Nymphalis antiopa". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ "Camberwell Arts Festival". Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Home page – Blue Elephant Theatre". blueelephanttheatre.co.uk.

- ^ "Art in the East End: Mat Collishaw". hungertv.com. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Architects Journal June 2012 http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/caseyfierro-unwraps-anish-kapoor-studio/8625145.article

- ^ Lucky Kunst, The Rise and Fall of Young British Art. Aurum Press, London 2012, p. 11 ISBN 1845133900

- ^ 'Camberwell', Old and New London: Volume 6 (1878), pp. 269–286 Date accessed: 13 February 2011.> http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45281

- ^ "Welcome to Camberwell Guide". Southlondonguide.co.uk. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "The Ruskin Window". Stgilescamberwell.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Camberwell history – Southwark's historic villages". Southwark.gov.uk. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Paul Delany, to In the Year of Jubilee. London: J.M. Dent, 1994.

- ^ Paul Delany, "Introduction".

- ^ Mount, Ferdinand, "The Go-Away Bird", The Spectator (review of Muriel Spark, the Biography by Martin Stannard), archived from the original on 18 June 2010, retrieved 13 April 2016

- ^ "The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters review – satire meets costume drama". The Guardian. 15 August 2014.

- ^ Wight, Colin. "Virtual books: images only – The Notebook of William Blake: Introduction". bl.uk.

- ^ Göran – 4 December 2011. "The 100 best London songs – Songs about London". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Braidwood - 29 June 2018 (29 June 2018). "Florence Welch's guide to South London – the real-life places referenced in her new album". NME. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ [1] Archived 22 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Camberwell Fair]

- ^ "CFFF Vimeo Films". Camberwell Arts.

- ^ Blackfriars Bridge – Loughborough Junction Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today, UK.

- ^ The Buildings of England London 2: South, Second Edition 1983, page 625

- ^ Transport for London: Bakerloo line extension Archived 23 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 5 January 2016

- ^ a b c "London's Rail & Tube Services" (PDF). Transport for London and National Rail. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015.

- ^ "The Enid Blyton Society". enidblytonsociety.co.uk.

- ^ "Living in Camberwell: area guide to homes, schools and transport links". 22 August 2014.

- ^ Rühle, Otto (2013). Karl Marx: His Life and Work. Routledge. p. 169.

- ^ McKie, David (7 January 2018). "Peter Preston obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ "Zoe Williams: My neighbour, the Leopard Man of Peckham". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Amy Grier (31 July 2009). "Florence Welch – My London". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Jenny Agutter on Call the Midwife, the Railway Children and the pitfalls of Hollywood". Radio Times. 18 January 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Actress Jenny Agutter joins forces with Camberwell community leaders to help boost local businesses featuring Denmark Hill Railway Station – South London News". Londonnewsonline.co.uk. 16 August 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Kirby, Terry (30 November 2006). "Syd Barrett's last remnants sold in frenzy of bidding". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon's American Nephew – Shannon Selin". 20 February 2015.

- ^ Association, The Football. "Back to his roots!". The Football Association.

- ^ Beasley, John D. (15 November 2010). Camberwell Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445627267 – via Google Books.

- ^ "AFC Camberwell". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Jeremy Bowen (22 June 2019). "Jeremy Bowen on Twitter: "As a Camberwell resident since the 1980s, I'd like to say that mostly it's calm and peaceful. Though there can be some police activity at night."". Retrieved 27 May 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Thomas Brodie-Sangster: I'd like an evil role, actually". 2 September 2015.

- ^ Julian Amery and J. L. Garvin, The life of Joseph Chamberlain, Six volumes, Macmillan, 1932–1969.

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837–1915 for Florence Eliza Collingbourne: 1880, Q1-Jan–Feb–Mar – Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Albert Houthuesen Chronology".

- ^ Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 by Rupert Gunnis p.179

- ^ "Marianne Jean-Baptiste blue plaque".

- ^ Southwark News "DOUBLE PLAQUE IN HERNE HILL FOR HOLLYWOOD STARS STANLEY AND IDA LUPINO"[2]

- ^ Nolan, Larissa (9 May 2021). "David McSavage: I like having the status of an outsider". The Times. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Back to the future". The Guardian. 12 March 2006.

- ^ "Birthdays". The Guardian. 22 July 2014. p. 37.

- ^ Sullivan, John. "James Ring". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "Rust, William Charles (1903–1949), political activist and journalist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40599. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Cawley, Richard (9 October 2018). "South Londoner Jadon Sancho could make full England debut – at the age of just 18". South London Press. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Lowie, Robert H. "Edward B. Tylor." American Anthropologist, vol. 19, no. 2, 1917, p. 262. JSTOR, [3].

- ^ Hugman, Barry J., ed. (2010). The PFA Footballers' Who's Who 2010–11. Mainstream Publishing. p. 430. ISBN 978-1-84596-601-0.

- ^ London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813–1906 Record for Jonathan Whitcher – Ancestry.co.uk

- ^ Ryan, Francesca (4 June 2009). "Florence and the Machine interview: sound and vision". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

Further reading

edit- Richard Tames. Dulwich and Camberwell Past: With Peckham, London: Historical Publications, 1997. ISBN 978-0-94866-744-2