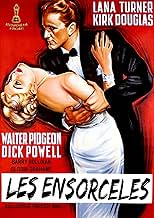

An unscrupulous movie producer uses an actress, a director and a writer to achieve success.An unscrupulous movie producer uses an actress, a director and a writer to achieve success.An unscrupulous movie producer uses an actress, a director and a writer to achieve success.

- Won 5 Oscars

- 7 wins & 7 nominations total

Jay Adler

- Mr. Z - Party Guest

- (uncredited)

Stanley Andrews

- Sheriff

- (uncredited)

Ben Astar

- Joe - Party Guest

- (uncredited)

Barbara Billingsley

- Evelyn Lucien - Costumer

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaAt 9 minutes and 32 seconds, Gloria Grahame's performance in this movie became the shortest to ever win an Oscar. She held the record until 1976, when Beatrice Straight won for her 5 minute performance in Network (1976).

- GoofsThe story takes place over an 18-year period, roughly 1934-1952, but the hairstyles and clothing of all the women, from beginning to end, are strictly 1952.

- Alternate versionsAlso available in a computer colorized version.

- ConnectionsFeatured in The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959)

Featured review

During this time in the early 50s there were quite a number of Hollywood pictures which scrutinised and often satirised Hollywood itself. The old studio system had been seriously weakened in the war years, the young crop of independent producers and writer-directors were gaining ever more prominence, and the dream factory as a whole had become a little more introspective, not to mention cynical. But while Sunset Boulevard, All About Eve (about the theatre, but the point carries through) and Singin' in the Rain aimed their sights at the injustice and hypocrisy of the star system, The Bad and the Beautiful takes on the thorny issue of creative control.

The Bad and the Beautiful is referenced extensively in auteurist Martin Scorsese's 1995 documentary on American movies, as an explanation of the antagonism between a producer's commercial drive and a director's artistic one. However it is far from a validation of auteur theory, for while it emphasises the importance of the director's role, it also points out (quite correctly) the equally crucial contributions of the writer and the producer himself. Incidentally the actual producer of The Bad and the Beautiful is John Houseman, primarily an actor who really only dabbled (albeit quite successfully) in production, and thus someone who could perhaps afford to snipe from the sidelines. Oddly enough screenwriter Charles Schnee would also turn to producing soon after this. He certainly shows extensive insider knowledge of the industry.

The director of The Bad and The Beautiful is Vincente Minnelli, a man whose flowing and extravagant style was put to best use in the musical genre, and although he was certainly competent in drama he does tend to overdo things a little for the form. One typically impressive Minnelli manoeuvre is the lengthy tracking shot at the party about fifteen minutes in, in which the camera is "carried" from one character to the next, while the careful arrangement of extras draws our eyes from one point of focus to another, a woman singing beautifully yet unnoticed in one corner, while a gossipy starlet is surrounded by a gaggle of admirers in another. Minnelli's tendency to keep all the characters in shot together during dialogue scenes means there is no need for back-and-forth editing. When there is a cut it is a meaningful jump, such as the close-up when Sullivan is told he won't be directing Shield's first big picture. Ultimately though the elaborate nature of Minnelli's direction is disproportionate to the needs of the picture, and a more stripped-down approach could have intensified the drama.

Another lesson The Bad and the Beautiful teaches us, both through its plot and its own example, is the importance of the right actors in a production. The majority of players in this large ensemble cast tend towards a uniform competence. People like Walter Pidgeon, Barry Sullivan and Vanessa Brown give steady, solid performances, not outstanding but apt to their characters. Dick Powell has a neat writer-ish cynicism to him, and it is only him and the vivacious Gloria Grahame that threaten to steal the show. A gratingly melodramatic Lana Turner is the only conspicuously bad player. However at the heart of The Bad and the Beautiful lies the powerful turn by Kirk Douglas. Douglas plays Shields with the mix of realism and exaggeration of a larger-than-life character, capturing the producer's boyish enthusiasm and exposing his inner fragility in a way that draws attention and lingers in the mind.

And it is here that we can see the picture's real worth. It is all very well making an accurate and incisive behind-the-scenes study of Hollywood's methods and morals, but to have any point the picture should also be an engaging and entertaining piece of storytelling. The Bad and the Beautiful is not especially romantic or funny or suspenseful, and yet it was a big hit, being the second-highest grossing picture of 1952. It seems the best thing this picture has going for it is the very character of Shields himself, who as written by Schnee and played by Douglas is both a fascinating and, yes, sympathetic individual. And the overriding message seems to be that, while producers tend to be a rather dysfunctional lot, it is their drive and efficiency that is behind many of the best things in movies. The picture's original title Tribute to a Bad Man is eminently better than the one it got saddled with. Jonathon Shields is clearly not a nice person, but through its compelling portrayal The Bad and the Beautiful salutes him.

The Bad and the Beautiful is referenced extensively in auteurist Martin Scorsese's 1995 documentary on American movies, as an explanation of the antagonism between a producer's commercial drive and a director's artistic one. However it is far from a validation of auteur theory, for while it emphasises the importance of the director's role, it also points out (quite correctly) the equally crucial contributions of the writer and the producer himself. Incidentally the actual producer of The Bad and the Beautiful is John Houseman, primarily an actor who really only dabbled (albeit quite successfully) in production, and thus someone who could perhaps afford to snipe from the sidelines. Oddly enough screenwriter Charles Schnee would also turn to producing soon after this. He certainly shows extensive insider knowledge of the industry.

The director of The Bad and The Beautiful is Vincente Minnelli, a man whose flowing and extravagant style was put to best use in the musical genre, and although he was certainly competent in drama he does tend to overdo things a little for the form. One typically impressive Minnelli manoeuvre is the lengthy tracking shot at the party about fifteen minutes in, in which the camera is "carried" from one character to the next, while the careful arrangement of extras draws our eyes from one point of focus to another, a woman singing beautifully yet unnoticed in one corner, while a gossipy starlet is surrounded by a gaggle of admirers in another. Minnelli's tendency to keep all the characters in shot together during dialogue scenes means there is no need for back-and-forth editing. When there is a cut it is a meaningful jump, such as the close-up when Sullivan is told he won't be directing Shield's first big picture. Ultimately though the elaborate nature of Minnelli's direction is disproportionate to the needs of the picture, and a more stripped-down approach could have intensified the drama.

Another lesson The Bad and the Beautiful teaches us, both through its plot and its own example, is the importance of the right actors in a production. The majority of players in this large ensemble cast tend towards a uniform competence. People like Walter Pidgeon, Barry Sullivan and Vanessa Brown give steady, solid performances, not outstanding but apt to their characters. Dick Powell has a neat writer-ish cynicism to him, and it is only him and the vivacious Gloria Grahame that threaten to steal the show. A gratingly melodramatic Lana Turner is the only conspicuously bad player. However at the heart of The Bad and the Beautiful lies the powerful turn by Kirk Douglas. Douglas plays Shields with the mix of realism and exaggeration of a larger-than-life character, capturing the producer's boyish enthusiasm and exposing his inner fragility in a way that draws attention and lingers in the mind.

And it is here that we can see the picture's real worth. It is all very well making an accurate and incisive behind-the-scenes study of Hollywood's methods and morals, but to have any point the picture should also be an engaging and entertaining piece of storytelling. The Bad and the Beautiful is not especially romantic or funny or suspenseful, and yet it was a big hit, being the second-highest grossing picture of 1952. It seems the best thing this picture has going for it is the very character of Shields himself, who as written by Schnee and played by Douglas is both a fascinating and, yes, sympathetic individual. And the overriding message seems to be that, while producers tend to be a rather dysfunctional lot, it is their drive and efficiency that is behind many of the best things in movies. The picture's original title Tribute to a Bad Man is eminently better than the one it got saddled with. Jonathon Shields is clearly not a nice person, but through its compelling portrayal The Bad and the Beautiful salutes him.

- How long is The Bad and the Beautiful?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $1,558,000 (estimated)

- Gross worldwide

- $2,025

- Runtime1 hour 58 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content