David Michael Gordon "Davey" Graham (originally spelled Davy Graham) (26 November 1940 – 15 December 2008) was a British guitarist and one of the most influential figures in the 1960s British folk revival. He inspired many famous practitioners of the fingerstyle acoustic guitar such as Bert Jansch, Wizz Jones, John Renbourn, Martin Carthy, John Martyn, Paul Simon and Jimmy Page, who based his solo "White Summer" on Graham's "She Moved Through the Fair". Graham is probably best known for his acoustic instrumental "Anji" and for popularizing DADGAD tuning, later widely adopted by acoustic guitarists.[1]

Davey Graham | |

|---|---|

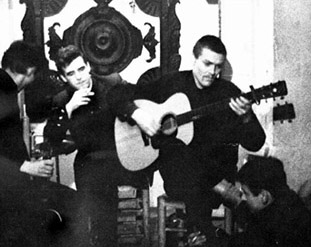

Graham performing at The Troubadour with Lou Killen | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | David Michael Gordon Graham |

| Also known as | Davy Graham |

| Born | 26 November 1940 Market Bosworth, Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 15 December 2008 (aged 68) London, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar, classical guitar, sarod, lute, oud, vocals |

| Years active | 1959–2008 (49 years) |

| Labels |

|

| Website | davygraham.com |

Biography

editEarly life

editGraham was born in Market Bosworth, Leicestershire, England,[2][page needed][3] to a Guyanese mother, Winifred (known as Amanda) and a Scottish father, Hamish, a teacher from the Isle of Skye.[4][5] He grew up in Westbourne Grove, in the Notting Hill Gate area of London.[5] Although he never had any music theory lessons, he learnt to play the piano and harmonica as a child and then took up the classical guitar at the age of 12.[6] As a teenager he was strongly influenced by the folk guitar player Steve Benbow, who had travelled widely with the army and played a guitar style influenced by Moroccan music.[7]

"Anji"/"Angi"

editAt the age of 19, Graham wrote what is probably his most famous composition, the acoustic guitar solo "Angi" (sometimes spelled "Anji": see below). Colin Harper credits Graham with single-handedly inventing the concept of the folk guitar instrumental.[2][page needed] "Angi", named after his then girlfriend, appeared on his debut EP, 3/4 AD, in April 1962. The tune spread through a generation of aspiring guitarists, changing its spelling as it went. Before the record was released, Bert Jansch had learnt it from a 1961 tape borrowed from Len Partridge. Jansch included it on his 1965 debut album as "Angie". The spelling Anji became the more widely used after it appeared on Simon & Garfunkel's 1966 album Sounds of Silence.[8] In 1969, the same name for Chicken Shack's 100 Ton Chicken was used.[citation needed]

"Anji" soon became a rite of passage for many acoustic finger-style guitarists. Arlen Roth has recorded "Anji" on two of his albums.[citation needed]

Some other musicians of note who have covered "Anji" are John Renbourn, Lillebjørn Nilsen, Gordon Giltrap, Clive Carroll and the anarchist group Chumbawamba, who used the guitar piece as a basis for their anti-war song "Jacob's Ladder (Not in My Name)".[9]

"Angi" is the second track on the first CD of the Topic Records 70th anniversary box set Three Score and Ten.[citation needed]

Folk fame

editGraham came to the attention of guitarists through his appearance in a 1959 broadcast of the BBC TV arts series Monitor, produced by Ken Russell and titled Hound Dogs and Bach Addicts: The Guitar Craze, in which he played an acoustic instrumental version of "Cry Me a River".[10] During the 1960s, Graham released a string of albums of music from all around the world in many genres. 1964's Folk, Blues and Beyond and the following year's collaboration with the folk singer Shirley Collins, Folk Roots, New Routes, are frequently cited[by whom?] among his most influential albums. Large as Life and Twice as Natural includes his cover of Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides, Now" alongside explorations of Eastern modes.

Graham appears (uncredited) playing guitar in a pub in Joseph Losey's 1963 film The Servant.[citation needed]

Retirement

editGraham married the American singer Holly Gwinn in the late 1960s and recorded the albums The Holly Kaleidosope and Godington Boundary with her in 1970, shortly before Gwinn had to return to the US and he was unable to follow her, because of his visa problem due to a marijuana conviction.[5] He later described himself as having been "a casualty of too much self-indulgence",[10] becoming a heroin addict in imitation of his jazz heroes.[6] During this period, he taught acoustic guitar and also undertook charity work, particularly for various mental health charities. For several years he was on the executive council of Mind[10] and he was involved for some time with the mystic Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh).[citation needed]

In 1976, Graham recorded All That Moody, essentially a private pressing. He recorded two further groundbreaking albums for Kicking Mule, 1978's The Complete Guitarist and 1980's Dance For Two People.[citation needed]

He continued to play concerts, but dedicated the main thrust of his life to studying languages; he was fluent in Gaelic (taught by his native-speaking father),[5] French, and Greek and could hold his own in Turkish. He collected poems and folk songs and would regale his neighbours. After some time, he became increasingly disinhibited.

Rediscovery and death

editGraham was the subject of a 2005 BBC Radio documentary, Whatever Happened to Davy Graham?,[11] and in 2006 featured in the BBC Four documentary Folk Britannia.[12]

Many people sought out Graham over the years and tried to encourage him to return to the stage to play live; the last of this long line of seekers was Mark Pavey,[citation needed] who arranged some outings with guitarists and old friends including Bert Jansch, Duck Baker and Martin Carthy. These concerts were typically eclectic, with Graham playing a mix of acoustic blues, Romanian dance tunes, Irish pipe tunes, songs from South Africa and pieces by Bach.[5] His final album, Broken Biscuits, consisted of originals and new arrangements of traditional songs from around the world.[13]

Graham was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008 and died on 15 December of that year,[5] at his home in London.[14]

In November 2016, a blue plaque was installed at his birthplace, the former Bosworth Park Infirmary building.[3]

Influence

editGraham did not seek or achieve great commercial success,[10][15] though his music received positive critical feedback and influenced folk revival artists and fellow players such as Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Martin Carthy, Ralph McTell, Wizz Jones, John Martyn, Nick Drake, Ritchie Blackmore, and Paul Simon, as well as folk rock bands such as Fairport Convention and Pentangle.[citation needed]

Though Graham is commonly referred to as a folk musician, the diversity of his music shows strong influences from many genres. Elements of blues, jazz, and Middle Eastern music are evident throughout his work.[citation needed]

Martin Carthy described Graham as "...an extraordinary, dedicated player, the one everyone followed and watched – I couldn't believe anyone could play like that," while Bert Jansch claimed that he was "courageous and controversial – he never followed the rules." Ray Davies maintained that the guitarist was "the greatest blues player I ever saw, apart from Big Bill Broonzy".[5]

According to George Chkiantz, "What impressed me with Davy Graham...was he played the guitar fretboard somehow as if it was a keyboard. There was a kind of freedom. You weren't conscious of him using chord shapes at all: his fingers just seemed to run around with complete freedom on the fretboard."[16]

DADGAD

editOne of Graham's lasting legacies is the DADGAD (open Dsus4) guitar tuning, which he popularised in the early 1960s.[17] While travelling in Morocco, he developed the tuning so he could better play along with and translate the traditional oud music he heard to guitar. Graham then went on to experiment playing traditional folk pieces in DADGAD tuning, often incorporating Indian and Middle Eastern scales and melodies. A good example is his arrangement of the traditional air "She Moved Through the Fair", which he recorded live at the Troubadour in Earl's Court in 1964. The tuning provides freedom to improvise in the treble, while maintaining a solid underlying harmony and rhythm in the bass—though it restricts the number of readily playable keys. While guitarists used "non-standard" or "non-classical" tunings before this (e.g., open E and open G in common use by blues and slide guitar players) DADGAD introduced a new "standard" tuning.[10] Many guitarists now use the tuning, especially in folk and world music.[citation needed]

Discography

editStudio albums

edit- The Guitar Player (1963)

- Folk, Blues and Beyond (1965)

- Midnight Man (1966)

- Large as Life and Twice as Natural (1968)

- Hat (1969)

- Holly Kaleidoscope (1970)

- Godington Boundary (1970) (with Holly Gwinn)

- All That Moody (1976)

- The Complete Guitarist (1978)

- Playing in Traffic (1991)

- Broken Biscuits (2007)

EPs

editLive albums

edit- After Hours (1997)[20]

Compilations

edit- Dance for Two People (1979)

- Folk Blues and All Points in Between (1985)

- Fire in the Soul (1999)

- The Best of Davy Graham (A Scholar & A Gentleman) (2009)

- Anthology-Lost Tapes 1961–2007 (2012)

Collaborations

edit- Folk Roots, New Routes (1964) with Shirley Collins

Bibliography

edit- Harper, Colin (2005), Irish Folk, Trad and Blues: a Secret History

- Harper, Colin (2006), Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-8725-6

- Hodgkinson, Will (2005). Article in The Guardian; Friday, 15 July 2005.

- The Times (2008). Obituary published in The Times, 22 December 2008, p. 50.[21]

- Young, Rob (2010), "Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's visionary music"

References

edit- ^ The DADGAD article, for example, lists users of this tuning, including Mícheál Ó Domhnaill, Dáithí Sproule, Russian Circles, Stan Rogers, Jimmy Page, Artie Traum, Pierre Bensusan, Eric Roche, Laurence Juber, Tony McManus, Bert Jansch, Richard Thompson, Dick Gaughan, Imaad Wasif, Jeff Tweedy, Paul McSherry, DEPAPEPE, Ben Chasny and Trey Anastasio.

- ^ a b Harper, Colin (August 2006). Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-8725-5.

- ^ a b "Folk musician Davy Graham honoured with birthplace plaque". BBC News. 26 November 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (December 2022). "Midnight Man". Uncut: 60.

- ^ a b c d e f g Denselow, Robin (17 December 2008). "Obituary: Davey Graham". The Guardian. London. p. 32.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Davy Graham". The Telegraph. London. 18 December 2008.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (15 July 2005). "Davey Graham". The Guardian.

- ^ "Sounds Of Silence". The Official Simon & Garfunkel Site. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Gill, Andy (2 August 2002). "Album: Chumbawamba - Readymades, Republic/Universal". The Independent. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Obituary of Davey Graham". The Times. 22 December 2008. p. 50.

- ^ "BBC Radio 6 Music - Whatever Happened to Davy Graham?". BBC. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Folk Britannia - Episode guide". BBC. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Davy Graham". Davy Graham. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (19 December 2008). "Davy Graham, Influential Guitarist, Dies at 68". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Davey Graham interview".

I never wanted to have a following. I was never interested in the big time, just to be good at what I was doing.

- ^ Sean Egan, Not Necessarily Stoned But Beautiful, Unanimous Ltd, 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Irwin, Colin (16 June 2011). "Davey Graham invents DAGDAD". The Guardian. London.

- ^ With Alexis Korner, guitar, on one track.

- ^ As The Thameside Four and Davy Graham.

- ^ Recorded at Hull University in 1967.

- ^ "Obituary". Timesonline.com. Retrieved 28 February 2015.[dead link]

External links

edit- Official website

- Article by John Renbourn and discography at Folk Blues & Beyond

- Interview given to www.terrascope.co.uk