The Diocese of Cleveland (Latin: Dioecesis Clevelandensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory, or diocese, of the Catholic Church in northeastern Ohio in the United States. As of September 2020[update], the bishop is Edward Malesic.[2] The Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, located in Cleveland, is the mother church of the diocese.

Diocese of Cleveland Dioecesis Clevelandensis | |

|---|---|

Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

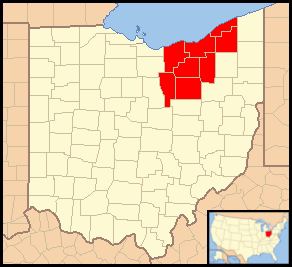

| Territory | The counties of Ashland, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain, Medina, Summit and Wayne in northeastern Ohio. |

| Ecclesiastical province | Cincinnati |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 3,414 sq mi (8,840 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2019) 2,774,113 682,948 (24%) |

| Parishes | 185 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | April 23, 1847 (177 years ago) |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist |

| Patron saint | St. John the Evangelist |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Edward Charles Malesic |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Dennis Marion Schnurr |

| Auxiliary Bishops | Michael G. Woost |

| Bishops emeritus | Roger William Gries (O.S.B.)[1] |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| dioceseofcleveland.org | |

The Diocese of Cleveland is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Cincinnati.

Territory

editThe Diocese of Cleveland is currently the 17th-largest diocese in the United States by population, encompassing the counties of Ashland, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain, Medina, Summit, and Wayne.

History

editEarly history

editDuring the 17th century, present day Ohio was part of the French colony of New France. The Diocese of Quebec, had jurisdiction over the region. However, unlike other parts of the future American Midwest, there were no attempts to found Catholic missions in Ohio.

In 1763, Ohio Country became part of the British Province of Quebec, forbidden from settlement by American colonists. After the American Revolution ended in 1783, Pope Pius VI erected in 1784 the Prefecture Apostolic of the United States, encompassing the entire territory of the new nation. In 1787, the Ohio area became part of the Northwest Territory of the United States. Pius VI created the Diocese of Baltimore, the first diocese in the United States, to replace the prefecture apostolic in 1789.[3][4]

In 1808, Pope Pius VII erected the Diocese of Bardstown in Kentucky, with jurisdiction over the new state of Ohio along with the other midwest states. Pope Pius VII on June 19, 1821, erected the Diocese of Cincinnati, taking all of Ohio from Bardstown.[5]

Diocese of Cleveland

edit1840 to 1870

editPope Pius IX erected the Diocese of Cleveland on April 23, 1847, with territory taken from the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. At that point, the diocese included counties going west to Toledo and south to Youngstown He named Reverend Louis Rappe as the first bishop of Cleveland.

When Rappe took office, the diocese contained 42 churches and 21 priests; the first and only Catholic church in Cleveland was St. Mary's on the Flats.[6] He soon established the city's first parochial school, which doubled as a chapel.[7]

Rappe purchased an episcopal residence in 1848, founding a seminary there. He laid the cornerstone of St. John's Cathedral in 1848. In 1849, Rappe went to Europe to recruit clergy for the diocese. He returned in 1850 with four priests, five seminarians, two Sisters of Charity and six Ursuline nuns.[8] The Daughters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary opened St. Mary's Orphan Asylum for Females in 1851. Rappe consecrated St. John's Cathedral on November 7, 1852. The Sisters of Charity opened St. Vincent's Asylum for Boys in 1852.[9] He also introduced the Grey Nuns to the diocese in 1856.

In 1865, Rappe established St. Vincent Charity Hospital, the first public hospital in Cleveland.[10] He brought in the Good Shepherd Sisters (1869), the Little Sisters of the Poor (1870), the Friars Minor (1867) and the Jesuits (1869),[8] and organized the Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine as a new congregation.[11] Rappe retired in 1870 after 33 years as bishop of Cleveland.

1870 to 1900

editIn 1872, Pope Pius IX appointed Reverend Richard Gilmour of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati as the second bishop of Cleveland. As bishop, Gilmour founded The Catholic Universe newspaper in 1874. In 1877, the Cuyahoga County auditor announced plans to tax Catholic churches and schools. Gilmour fought the auditor in court, winning his case six years later.[12] He was also wary of the public school system.[13] He established St. Ann's Asylum and Maternity Home,[14] St. Michael Hospital,[15] and St. John Hospital.In 1882, Gilmour condemned the Ladies Land League chapter in Cleveland.. Founded in Ireland, the League was a women's organization that assisted tenants being evicted from their homes.[16] After Gimour died in 1891, Pope Leo XIII named Reverend Ignatius Horstmann of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia as the new bishop of Cleveland.

Horstmann founded the following institutions in the diocese:

- Loyola High School in Cleveland (1902),

- St. John's College in Toledo (1898),

- St. Anthony Home for Working Boys in Cleveland.

- The Catherine Horstmann Home in Cleveland for homeless women.[17]

In the early 1890s, Horstmann faced a schism within the Diocese of Cleveland. Polish parishioners at St. Stanislaus Parish in Cleveland, led by Reverend Anton Kolaszewski, were demanding more control over their parish and more sensitivity to their customs. Despite Horstmann's refusal, Kolaszewski continued to press for independence and accused the bishop of sexual abuse crimes. In 1892, Horstmann relieved Kolaszewski of his post. When the new pastor arrived at St. Stanislaus Church for his first mass, a brawl broke out among the parishioners. In 1894, a group of parishioners started a new independent parish, Immaculate Heart of Mary, with Kolaszewski as pastor; Horstmann excommunicated all of them. Years later, after the deaths of both men, the diocese accepted the new church.[18]

1900 to 1945

editIn 1907, Horstmann faced a second schism, this time with Slovenian Catholics. After removing Reverend Kasimir Zakrajsek as pastor of St. Vitus Parish in Cleveland, he faced violent protests. After the parish rectory was stoned, the replacement priest was forced to flee. Over 100 people were arrested. On September 22, 1907, 5,000 Polish protesters marched on Horstmann's residence, demanding Zakrajsek's reinstatement and home rule for St. Vitus.[19] Horstmann died in 1908. Also see: https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/737.

Pope Pius IX named Reverend John Farrelly of the Diocese of Nashville as bishop of Cleveland in 1909. The next year, Pius IX erected the Diocese of Toledo, removing the Toledo area counties from the Diocese of Cleveland. During his 12-year-long tenure as bishop, Farrelly improved the parochial school system; organized Catholic Charities; and erected 47 churches and schools, including Cathedral Latin High School in Chardon, Ohio.[20] During World War I, Farrelly was appointed by Cleveland Mayor Harry L. Davis to the Cleveland War Commission.[21] Farrelly also ordered English to be spoken at all German language churches and schools in the diocese.[22] Farrely served as bishop until his death in 1921.

Bishop Joseph Schrembs of the Diocese of Toledo was appointed bishop of Cleveland in 1921 by Pope Pius XI. In 1925, the pope presented the relics of St. Christine to Schrembs. Christine, a 13-year-old girl who died for her Catholic faith around 300 AD, was moved from the Roman catacombs to St. John's Cathedral in Cleveland. The diocese had previously donated money to the Vatican for the establishment of the House of Catacombs outside Rome.[23][24][25] During his tenure, Schrembs erected 27 parishes in Cleveland and 35 outside the city. In 1942, as Schrembs' diabetes worsened, Pope Pius XII named Bishop Edward Hoban from the Diocese of Rockford as Schrembs' coadjutor bishop to help him with his duties.[26] In 1943, Pius XII erected the Diocese of Youngstown. taking counties from the Youngstown area away from the Diocese of Cleveland.

1945 to 1980

editAfter Schrembs died in 1945, Hoban automatically succeeded him as bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland. As bishop, Hoban encouraged refugees displaced by World War II to settle in Cleveland.[27] He also established national and ethnic parishes, but insisted that their parochial schools only teach in English.[27] He helped rebuild and remodel St. John's Cathedral, and enlarged St. John's College, both in Cleveland.[28] Hoban centralized Parmadale Family Services, constructed additional nursing homes, and opened Holy Family Cancer Home in Parma, Ohio, a hospice for cancer patients.[28] Hoban opened a minor seminary and expanded the Newman Apostolate for Catholic students attending public universities and colleges.[28] During Hoban's 21-year-long tenure, the number of Catholics in the diocese increased from 546,000 to 870,000.[28] Hoban also established 61 parishes, 47 elementary schools, and a dozen high schools.[28] Pope Paul VI appointed Bishop Clarence Issenmann of the Diocese of Columbus as coadjutor bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland on October 7, 1964.[29] When Hoban died in 1966, Issenmann automatically became his replacement in Cleveland.

As bishop, Issenmann constructed the following schools in the diocese:

- Villa Angela Academy in Cleveland,

- Lake Catholic High School in Mentor

- Lorain Catholic High School in Lorain

- St. Vincent-St. Mary High School in Akron

In November 1968, Issenmann asked all adults attending mass in the diocese to sign petitions of support for Humanae vitae, Pope Paul VI's 1969 encyclical against artificial birth control. Issenmann was the only bishop in the country to make that request of parishioners.[30] issenmann retired in 1974 due to poor health. Pope Paul VI in 1974 named Auxiliary Bishop James Hickey of the Diocese of Saginaw as the new bishop of Cleveland. Six years later, in 1980, the pope named him as archbishop of the Archdiocese of Washington.

1980 to present

editJohn Paul II appointed Auxiliary Bishop Anthony Pilla to replace Hickey as bishop of Cleveland in 1980. In 2005, 36 lay members of the diocese sued Pilla, accusing him of allowing $2 million in diocesan funds to be stolen. The judge dismissed the lawsuit, saying that the plaintiffs did not have the legal standing to sue in this case.[31] After 26 years as bishop, Pilla resigned in 2006.

In 2004, Phila received an anonymous letter accusing Joseph Smith, the assistant treasurer for the diocese, of theft. After meeting with Pilla, Smith went on administrative lead and later resigned.[32][31][33] In 2005, 36 parishioners sued the diocese, claiming that Smith and two other diocesan officials had diverted $2 million of diocese funds to their own businesses.

On April 5, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI named Auxiliary Bishop Richard Lennon of the Archdiocese of Boston as the tenth bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland.

In August 2007 Smith and Anton Zgoznik, a hired consultant, were charged with 17 counts of money laundering and tax evasion. Smith steered contracts worth $17.5 to Zgonik, who gave Smith kickbacks of $784,000. Zgoznik was convicted in October 2007 of conspiracy to commit mail fraud and mail fraud.[34] In December 2008, Smith was acquitted of embezzlement, but convicted of tax evasion; he received one year in prison.[35]

In 2009, the diocese announced the closing or merging of 52 parishes, due to the shortage of priests, the migration of Catholics to the suburbs, and the financial difficulties of some parishes.[36] The diocese also closed or merged several number of parish schools.[37] The hardest hit were urban parishes in Cleveland, Akron, Lorain, and Elyria. Parishioners from 13 urban parishes appealed Lennon's action to the Congregation for the Clergy in Rome. In 2012, the Congregation for the Clergy overturned all 13 closings because Lennon did not follow proper procedure or canon law.[38] Lennon resigned in 2016 due to poor health.

Pope Francis in 2017 appointed Auxiliary Bishop Nelson J. Perez of the Diocese of Rockville Centre to replace Lennon. Three years later, the pope name Perez as archbishop of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. As of 2023, the current bishop of Cleveland is Bishop Edward C. Malesic of the Diocese of Greensburg, named by Francis in 2020.

Reports of sex abuse

editIn March 2002, Bishop Pilla published a list of 28 priests accused of sexual abuse of minors. Fifteen of them were active priests, whom Pilla suspended from ministry. Earlier that year, Cuyahoga County Prosecutor William Mason announced an investigation of sexual abuse of minors by diocesan priests.[39]

In July 2011, an Ohio man sued Pilla and the diocese, saying that their negligence allowed a priest to sexually abuse him when he was a boy.[40] The plaintiff said that Reverend Patrick O’Connor, a diocesan priest at St. Jude Parish in Elyria, abused him from 1997 to 1999. Pilla knew that O'Connor had abused a child during the 1980s at St. Joseph Parish in Cuyahoga Falls. The diocese settled with that victim in 2003 and sent O'Connor to another parish Elyria. He resigned from the priesthood in 2008. O'Connor pleaded guilty to corruption of a minor in 2009 and was sentenced to 90 days in prison.[40][41]

In July 2019, the diocese added 22 more names to its list of "credibly accused" clergy.[42]

In December 2019, Reverend Robert McWilliams, a diocesan priest, was arrested at St. Joseph Parish in Strongsville on four counts of possessing child pornography.[43] Bishop Perez had called for McWilliams's arrest, describing the case as a "painful situation."[44] McWilliams pleaded guilty in July 2021 to sex trafficking of youths, sexual exploitation of children and possession of child pornography. Sentenced to life in prison in November 2021, McWilliams committed suicide in February 2022.[45] A young man sued the diocese in March 2022, stating that he had been raped by McWilliams in 2018 in Strongsville. The plaintiff said that when he was 15, McWilliams paid him $200 for three sex acts. The plaintiff was one of the victims in the criminal case against McWilliams.[46]

In March 2023, four women sued the diocese, saying that they had been sexually and physically assaulted at the Parmadale Children’s Village in Parma. The abuse allegedly occurred over several decades before the facility closed in 2017. The plaintiffs said they were used sexually by one of the priests and by staff employees; one plaintiff said the staff forced her to have sex with other residents while they watched.[47]

In February 2024, the trial of former priest Luis J. Barajas began in Cuyahoga County.[48] He had been indicted in November 2023 on six counts of gross sexual imposition, being accused of inappropriately touching a 15-year-old girl with cancer while performing a “blessing” in Westlake in October 2023.[49] He was arrested in October 2023 and released in January 2024 after posting bond.[48] Despite being able to perform the blessing by this time, it is believed that Barajas had previously been removed from priesthood soon after he was accused in 1989 of sexually abusing juveniles in the Diocese of Harrisburg.[48] He had also been arrested in 2019 on charges of misconduct with a minor.[48]

Statistics

editAs of 2023, the Diocese of Cleveland had a population of approximately 613,000 Catholics and contained 185 parishes, three Catholic hospitals, three universities, two shrines (St. Paul Shrine Church and St. Stanislaus Church), and two seminaries (Centers for Pastoral Leadership).[50]

Bishops

editBishops of Cleveland

edit- Louis Amadeus Rappe (1847–1870)

- Richard Gilmour (1872–1891)

- Ignatius Frederick Horstmann (1891–1908)

- John Patrick Farrelly (1909–1921)

- Joseph Schrembs (1921–1945), appointed Archbishop ad personam by Pope Pius XII in 1939

- Edward Francis Hoban (1945–1966; coadjutor bishop 1942–1945), appointed Archbishop ad personam by Pope Pius XII in 1951

- Clarence George Issenmann (1966–1974; coadjutor bishop 1964–1966)

- James Aloysius Hickey (1974–1980), appointed Archbishop of Washington (Cardinal in 1988)

- Anthony Michael Pilla (1980–2006)

- Richard Gerard Lennon (2006–2016)

- Nelson Jesus Perez (2017–2020), appointed Archbishop of Philadelphia

- Edward Charles Malesic (2020–present)

Auxiliary Bishops of Cleveland

edit- Joseph Maria Koudelka (1907–1911), appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Milwaukee and later Bishop of Superior

- James A. McFadden (1922–1943), appointed Bishop of Youngstown

- William Michael Cosgrove (1943–1968), appointed Bishop of Belleville

- John Raphael Hagan (1946)

- Floyd Lawrence Begin (1947–1962), appointed Bishop of Oakland

- John Joseph Krol (1953–1961), appointed Archbishop of Philadelphia (Cardinal in 1967)

- Clarence Edward Elwell (1962–1968), appointed Bishop of Columbus

- John Francis Whealon (1961–1966), appointed Bishop of Erie and later Archbishop of Hartford

- Gilbert Ignatius Sheldon (1976–1992), appointed Bishop of Steubenville

- Michael Joseph Murphy (1976–1978), appointed Bishop of Erie

- James Anthony Griffin (1979–1983), appointed Bishop of Columbus

- James Patterson Lyke O.F.M. (1979–1990), appointed Archbishop of Atlanta

- Anthony Michael Pilla (1979–1980), appointed Bishop of Cleveland

- Anthony Edward Pevec (1982–2001)

- Alexander James Quinn (1983–2008)

- Martin John Amos (2001–2006), appointed Bishop of Davenport

- Roger William Gries, O.S.B. (2001–2013)

- Michael Gerard Woost, (2022–present)

Other affiliated bishops

edit- John Patrick Carroll, Bishop of Helena (1889–1904)

- Augustus John Schwertner, Bishop of Wichita in 1921 (1897–1910)

- Thomas Charles O'Reilly, Bishop of Scranton (1898–1927)

- Edward Mooney, titular Archbishop and Apostolic Delegate, and later Archbishop (ad personam) of Rochester and Archbishop of Detroit (Cardinal in 1946) (1909–1926)

- Charles Hubert Le Blond, Bishop of Saint Joseph (1909–1933)

- Michael Joseph Ready, Bishop of Columbus (1918–1944)

- John Patrick Treacy, Coadjutor Bishop and later Bishop of La Crosse (1918–1945)

- Joseph Patrick Hurley, Bishop of Saint Augustine (and Archbishop (ad personam) in 1949) (1919–1940)

- John Francis Dearden, Coadjutor Bishop and later Bishop of Pittsburgh and Archbishop of Detroit (Cardinal in 1969) (1932–1948)

- Paul John Hallinan, Bishop of Charleston and later Archbishop of Atlanta (1937–1958)

- Raymond Joseph Gallagher, Bishop of Lafayette in Indiana (1939–1965)

- Timothy P. Broglio, Apostolic Nuncio to the Dominican Republic and later Archbishop for the Military Services, USA (1977–2001)

- David John Walkowiak, Bishop of Grand Rapids (1979–2013)

- Neal James Buckon, Auxiliary Bishop for the Military Services, USA (1995–2011)

Churches

editEducation

editAs of 2023, the Diocese of Cleveland had 20 high schools and 86 elementary schools with a total enrollment exceeding 38,000 students.[50]

In 2023, the diocese stated that students and employees cannot show expressions of LGBTQ identity.[51] Several independent Catholic schools chose not to follow the policy.[52]

High schools

editClosed schools

edit- Lorain Catholic High School – Lorain (co-ed) Closed in 2004.

- Nazareth Academy – Parma Heights (girls), (Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph 1957–1980). Closed in 1980, Holy Name High School moved into its building.[53]

- Regina High School – South Euclid (girls), (Sisters of Notre Dame), Closed in 2010

- St. Augustine Academy – Lakewood (girls) Closed 2005. Now Lakewood Catholic Academy elementary school.

- St. Peter Chanel High School – Bedford (co-ed) (Marist Fathers 1957–1973); (Diocese of Cleveland 1973–2013). Closed in 2013

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Rinunce e Nomine: Rinuncia dell'Ausiliare di Cleveland (U.S.A.)" [Waivers and Nominations: Auxiliary Waiver of Cleveland (U.S.A.)] (PDF) (Press release) (in Italian). Holy See Press Office. November 1, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ "Administrator elected to oversee Diocese of Cleveland". Crux. February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ "Our History". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Freedom of Religion Comes to Boston | Archdiocese of Boston". www.bostoncatholic.org. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Shearer, Donald (June 1933). "Pontificia Americana: A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES 1784 -1884". Franciscan Studies. 11 (11): 343. JSTOR 41974134 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "ST. MARY'S ON-THE-FLATS". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University. May 22, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Clarke, Richard Henry. Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States.

- ^ a b Houck, George Francis (1887). The Church in Northern Ohio and in the Diocese of Cleveland from 1749 to 1890. Short & Forman.

- ^ The National Magazine; A Monthly Journal of American History. 1887.

- ^ "St. Vincent Charity Medical Center". St. Vincent Charity Medical Center. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ "Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine", The Catholic Church in the United States of America, Catholic Editing Company, 1914, p. 86 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "GILMOUR, RICHARD". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- ^ Brownson's Quarterly Review (Last Series, Vol. 1, 1873, "The Church above the State", p. 353-354). Quote: "Catholics are too timid; they seem to go upon the principle that, if they are tolerated, they are doing well. This is a mistake; if we let our rights go by default, we should not wonder if we lose them. We must be decided in our demands, and present a bolder front to our enemies. It is unjust to so organize the public schools that we cannot in conscience send our children to them, and then tax us for their support. As well create a State Church, and tax us for its support."

- ^ "St. Ann's Hospital, Cleveland", The Catholic Church in the United States of America, Catholic Editing Company, 1914, p. 87 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "St. Michael Hospital", Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Case Western Reserve University

- ^ "BISHOP GILMOUR WELCOMED.; HIS EUROPEAN TOUR--THE WRETCHEDNESS OF IRELAND DESCRIBED". The New York Times. February 3, 1883. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ "HORSTMANN, IGNATIUS FREDERICK". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- ^ Paul, Mackenzie. "Immaculate Heart of Mary Church - The Struggle for a Polish Church in Cleveland's Warszawa". Cleveland Historical. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ "BISHOP'S HOUSE BESIEGED.; 5,000 Angry Polish Parishioners Demand Return of Former Priest". The New York Times. September 23, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Rose, William Ganson (December 1990). Cleveland: The Making of a City. Kent State University Press.

- ^ Avery, Elroy McKendree (1918). A History of Cleveland and Its Environs: The Heart of New Connecticut. Lewis Publishing Company.

- ^ Callahan, Nelson J. and William F. Hickey. The Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland.

- ^ "Saint's Body". TIME Magazine. August 3, 1925. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012.

- ^ "St. Christine Relics". Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ "Kateri Tekakwitha: First Catholic Native American saint". BBC News. October 21, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ "SCHREMBS, JOSEPH". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University. May 11, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Callahan, Nelson J. and William F. Hickey. Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland.

- ^ a b c d e "Hoban, Edward Francis". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- ^ "Pope Appoints Successors To Two American Bishops". The New York Times. October 15, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ "Cleveland Bishop Requests Loyalty Oath on Pope's Edict". The New York Times. December 1, 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Maag, Christopher (August 20, 2007). "Cleveland Diocese Accused of Impropriety as Embezzlement Trial Nears". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Tobin, Mike; Dealer, The Plain (May 30, 2008). "Former Bishop Pilla testifies in kickback trial". cleveland. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Sheeran, Thomas J. "Former Bishop Pilla Takes Stand in Kick-Back Trial". www.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ "#08-1093: Former Chief Financial Officer of Catholic Diocese of Cleveland Sentenced to a Year and a Day in Prison for Tax Crimes (2008-12-11)". www.justice.gov. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Neff, Martha Mueller; Dealer, The Plain (December 12, 2008). "Diocese finance officer gets year Joseph Smith also must pay restitution". cleveland. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ "Reconfiguration Plan — Q & A". Diocese of Cleveland. March 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Diocese of Cleveland Reconfiguration Office - List of Closing/Merging Parishes. Retrieved on March 25, 2009. Archived copy at WebCite (February 15, 2013).

- ^ O'Malley, Michael (March 13, 2012). "Vatican reverses Cleveland Catholic Diocese's closing of 13 parishes". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Shaffer, Cory; clevel; .com (October 2, 2018). "Catholic Priest Sex Scandal: Will Cleveland-area residents ever get to know the names of priests accused in the past?". cleveland. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Diocese to face sexual battery allegations". Morning Journal. July 2, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Michael O'Malley, The Plain Dealer (January 5, 2010). "Former Cleveland Catholic Diocese priest begins jail sentence for sexual offense". cleveland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Catholic Diocese of Cleveland identifies 22 more clerics previously accused of sexual abuse". cleveland. June 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ "Cleveland priest charged with possessing child pornography".

- ^ "Cleveland Bishop calls arrest of Strongsville priest on child porn charges 'heart-wrenching' in statement from Rome". cleveland. December 6, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ John Caniglia, cleveland com (February 4, 2022). "Former Strongsville priest serving life sentence in prison for sexually exploiting boys dies". cleveland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ John Caniglia, cleveland com (March 29, 2022). "Man sues Catholic Diocese of Cleveland over rape allegations against former priest McWilliams". cleveland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Cory Shaffer, cleveland com (March 21, 2023). "3 women sue Parmadale, Catholic Diocese over sexual abuse allegations spanning decades". cleveland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dennis, Justin (November 15, 2023). "Former priest to stand trial on molestation charges". WJW. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Dennis, Justin (November 15, 2023). "Former priest charged with molesting girl, 15, in Westlake faces judge". WJW. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Catholic Diocese of Cleveland AT A GLANCE" (PDF). Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Buyakie, Bryce (September 13, 2024). "Catholic Diocese of Cleveland bars LGBTQ+ expression, support on school properties/". Akron Beacon Journal. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ "Some Catholic schools independent of the Cleveland Diocese appear to distance themselves from new LGBTQ policy". cleveland.com. September 26, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ "Saint Joseph Academy Academics". www.sja1890.org. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

External links

edit- Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland official website